Key Takeaways

- A rushed exit of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from government conservatorship risks higher mortgage rates and reduced housing affordability.

- Don’t fix what’s not broken: We believe that keeping Fannie and Freddie in conservatorship would ensure stability and liquidity, and is ultimately a better deal for the U.S. taxpayer.

- In our view, scaling back the GSEs’ role in housing finance would be easier if they stay in conservatorship than if they were privatized.

- If privatized, providing an explicit government MBS backstop is the only way to ensure there is no disruption to the mortgage market and to achieve other benefits, too.

Following President Donald Trump’s decisive victory in November, financial markets have responded in anticipation of potential policy changes under “Trump 2.0.” One of the starkest examples of these “Trump trades” is the outperformance of about $20 billion in outstanding equity and preferred stock in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, driven by speculation that these government-sponsored enterprises, or GSEs, might be released from over 16 years of government conservatorship – a move that could potentially benefit shareholders.

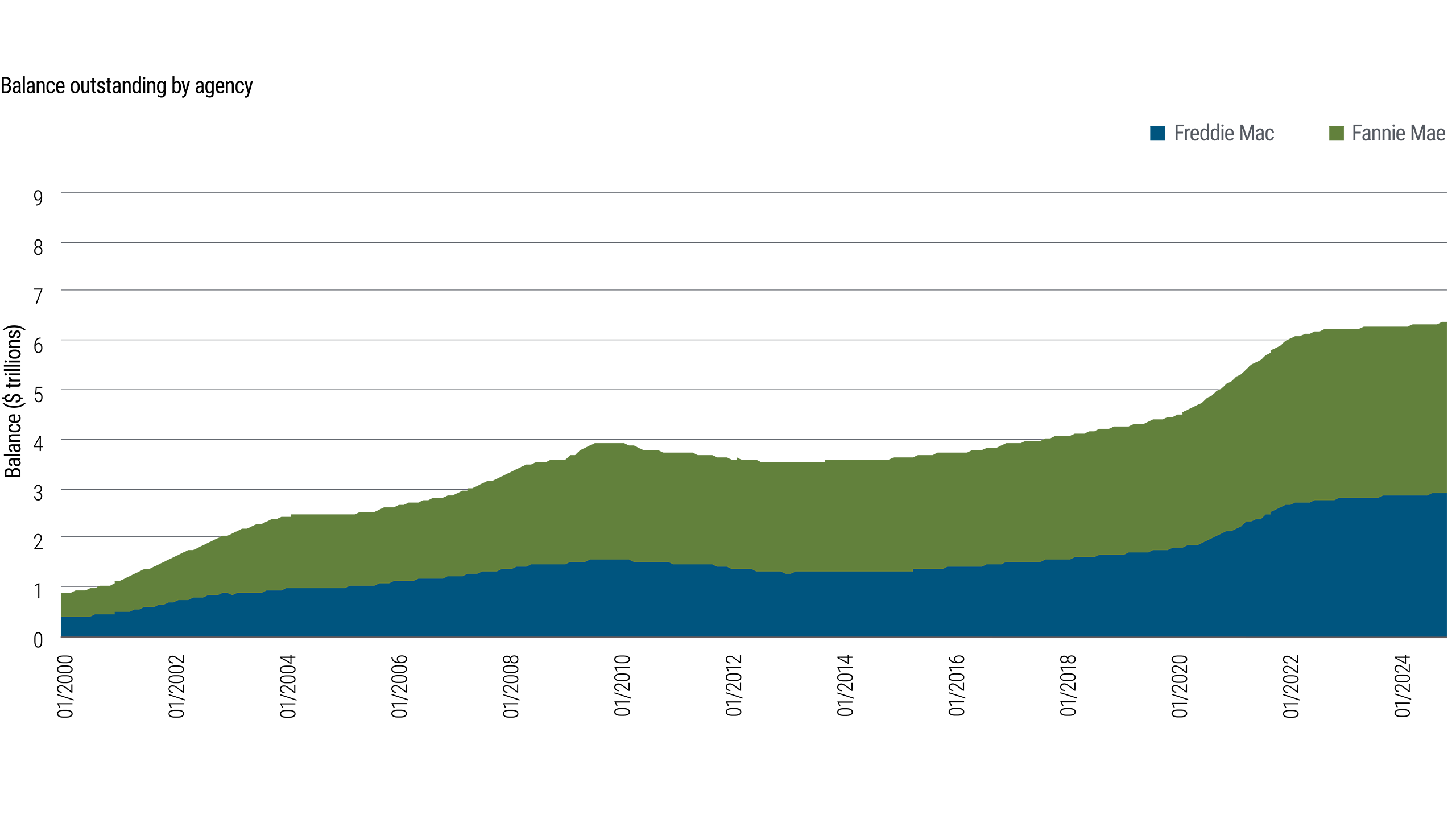

Regardless of what Washington decides, our focus at PIMCO, as one of the largest participants in the $6.6 trillion GSE, or agency mortgage-backed security (agency MBS), market,1 is to ensure on behalf of our clients that the deep, well-functioning mortgage market continues uninterrupted and, ideally, unaffected.

After all, the U.S. mortgage market is the envy of the world: It is the best-functioning and most liquid mortgage market globally, providing millions of American homebuyers access to the all-important 30-year fixed- rate mortgage, regardless of where they live. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac play an essential role, supporting about 70% of the U.S. mortgage market.2

If an exit from conservatorship is rushed and certain issues are not addressed – particularly as they relate to the government guarantee associated with the GSEs entering conservatorship during the global financial crisis in 2008 – many Americans could unwittingly face higher mortgage rates. This would come at a time when housing affordability is a major concern for everyday Americans.3

What is the policy objective?

While we sympathize with the desire to release the GSEs from conservatorship, we think policymakers should outline their precise objectives and consider the potential consequences, both intended and unintended, before proceeding.

The U.S. agency MBS market is currently liquid and well functioning

If the goal of policymakers is simply to have the GSEs continue to provide liquidity to the secondary mortgage market – and, by extension, to allow borrowers across the U.S. to maintain access to 30-year fixed-rate mortgage loans – the GSEs in conservatorship have been and continue to be exceedingly successful. Indeed, while in conservatorship, the agency MBS market has only become bigger and deeper (see Figure 1).

At the same time, reforms by the GSEs’ conservator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), have placed the GSEs on much firmer footing than they were prior to conservatorship, making them significantly less vulnerable to shocks by:

- Imposing strict limits on the size of the GSEs’ investment portfolios, a large source of the instability in 2008

- Subjecting the GSEs to much higher capital requirements relative to pre-conservatorship

- Introducing credit risk transfer (CRT) programs, which have allowed the GSEs to offload portions of their single-family mortgage credit risk to institutional investors4

Importantly, keeping the GSEs in conservatorship has also ensured that it is the government – or, more specifically, the taxpayer – who benefits from the gains and successes of the GSEs. This contrasts with the pre-2008 period, when GSE gains were privatized and accrued to shareholders while losses were ultimately socialized and borne by taxpayers.

Reducing the government’s footprint may be easier with the GSEs in conservatorship

If, however, the objective is to reduce the government’s footprint in the housing finance market and crowd in private capital – a laudable goal, from our perspective – we believe there are relatively straightforward reforms that can be pursued that do not require an act of Congress and similarly do not necessitate a release of the GSEs from conservatorship. In fact, some would argue that reforms are significantly easier to implement while the GSEs remain in conservatorship, given the legal questions that would arise if the GSEs were released.5

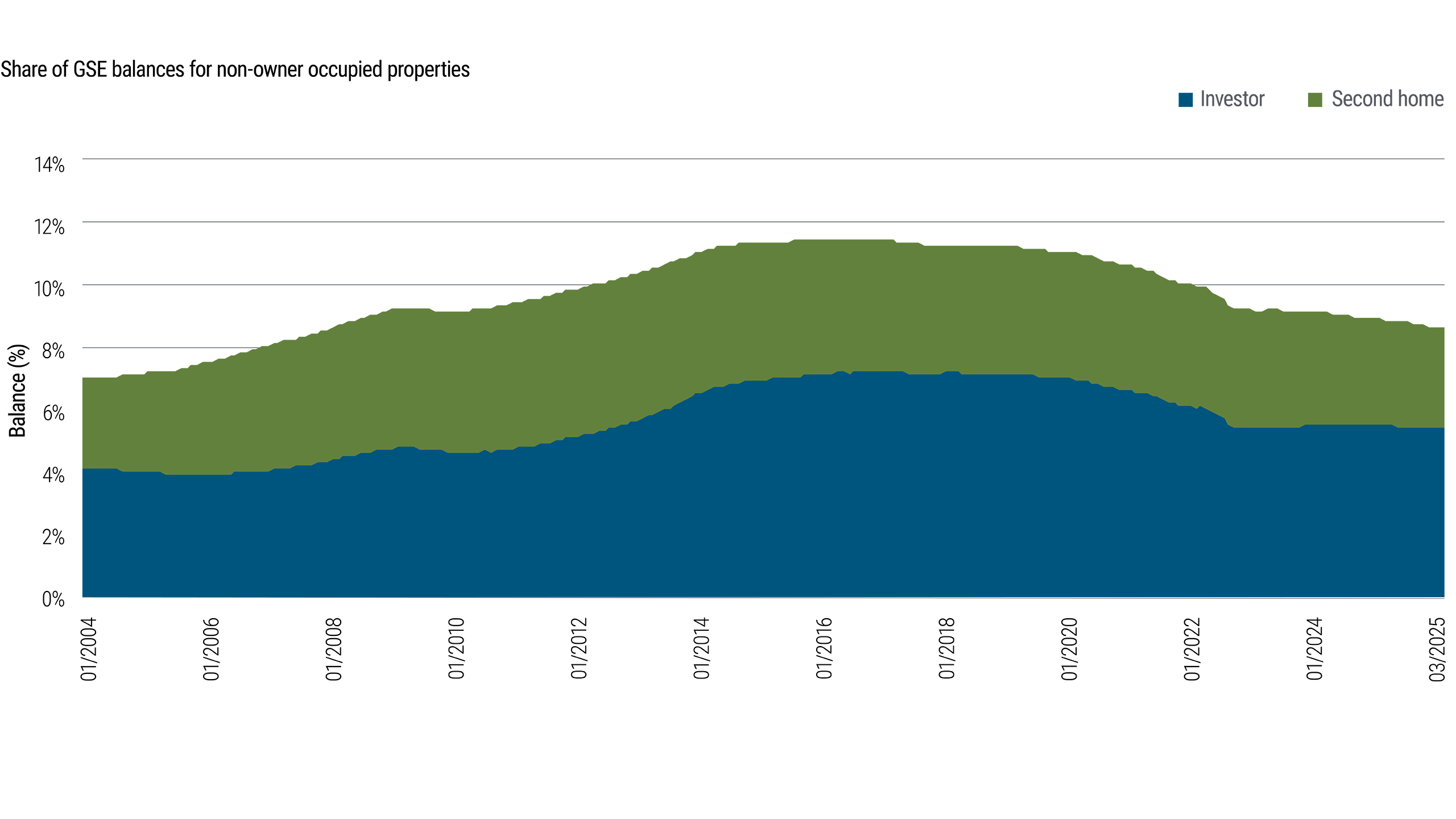

The most straightforward of these reforms – one not requiring release or an act of Congress – would be to align the activities of the GSEs with Congress’ original intent: to provide access exclusively to primary homeownership for average Americans. As they stand now, the GSEs also guarantee mortgages for second homes, vacation homes and investment properties, and support cash-out refinancings (see Figure 2). Yet borrowers in these products typically have high incomes and elevated FICO scores and have already accessed primary homeownership – the original policy goal of the GSEs. What is more, there is ample appetite from private capital to participate in these areas, but it is currently crowded out by the GSEs.

Along these lines, we thought the changes initiated by then-FHFA Director Mark Calabria in January 2021 to limit the number of mortgage loans associated with second homes and investment properties eligible for purchase by the GSEs were a step in the right direction. However, these changes were overturned by the incoming Biden administration.6

Who benefits from the release? Not necessarily taxpayers

There is also the question of who may benefit from releasing the GSEs from conservatorship. We see how release could benefit preferred shareholders, but we do not necessarily see how release – especially if it has an “implicit guarantee” of government support – necessarily benefits taxpayers.

Indeed, the assumption that the government would still be responsible for GSE losses even after release, without any real, durable compensation for that risk, raises the question of why policymakers would release them in the first place. In other words, if the taxpayer is ultimately going to be liable for the losses of the GSEs in a downturn, why shouldn’t the taxpayer reap the gains of the GSEs during heady times as well? If the GSEs are released but the government remains accountable to come to their rescue, wouldn’t taxpayers ultimately be the biggest loser (once again) by seeing GSE gains privatized but losses socialized?

An explicit government guarantee would ensure no disruption to the mortgage market

Should policymakers decide to privatize Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, we believe an explicit government guarantee from Congress (likely funded by the GSEs) would ensure the least amount of disruption, if any, to the mortgage market and provide continued, unabated access to the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. Indeed, a recent market participant survey suggests that an explicit government guarantee could actually decrease existing mortgage rates – a welcome development, given concerns about housing affordability.7

An explicit government guarantee would come with other benefits as well: not only the ability to directly compete with Ginnie Mae, which has an explicit guarantee, but also the same preferential capital treatment that Ginnie Mae securities currently enjoy under the Basel rules. Specifically, these include a 0% risk-weighted asset (RWA) calculation instead of the current 20% requirement, and treatment as a Level 1 asset rather than a Level 2 asset under the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) requirement.8 In practice, this could free up substantial capital in the banking sector, providing a potential tailwind to economic growth.

At the same time, a failure to provide an explicit guarantee is a choice in and of itself and would require the market to rely on assurances and assumptions that the government would once again step in should Fannie and Freddie become troubled.

While that may well be true, the Preferred Stock Purchase Agreement (PSPA) – which would presumably pledge ongoing government support post-release – is inherently political. As we saw as recently as January, at the tail end of the Biden Administration, the PSPA can be changed to suit the political and policy objectives of a particular administration, making any pledges regarding capital uncertain.9 While changes matter less in conservatorship, if the GSEs were released, they would inject uncertainty about the reliability of government support.

In other words, as a former CEO of Freddie Mac, Don Layton, put it: “A future administration could change the relevant regulations and PSPA amendments, making market confidence more fragile. By contrast, legislative changes are viewed as more permanent.”10

Even if the capital pledged through the PSPA were ironclad (which it isn’t), investors would still be forced to assume that the government would rescue Fannie and Freddie should the GSEs face difficulty. Indeed, in times of trouble, this could be more a question of when rather than if, given $6.6 trillion of effectively explicit guaranteed agency MBS outstanding as of February 2025.1 In other words, in times of trouble, the GSEs could easily exhaust the capital pledged through the PSPA.

Questions we believe policymakers should address before moving forward with release

Broadly, we believe that anything short of an explicit, legislated government guarantee would inject at least some uncertainty into the mortgage market. This would manifest in higher mortgage rates, though the magnitude of the increase is uncertain.

However, if policymakers plan to release the GSEs from conservatorship without an explicit, congressionally provided guarantee, we would encourage them to consider several open-ended questions:

- What does the to-be-announced (TBA) market look like post-release without an explicit guarantee, and what are the implications for the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage market?

The TBA market is one of the key tenets of today’s deep, liquid mortgage market, as it allows mortgage originators – and therefore borrowers – to lock in future mortgage rates and access the same mortgage rate regardless of where they live and irrespective of the underlying factors in the housing markets they reside in. Without an explicit guarantee backing Fannie and Freddie loans, MBS investors in the TBA market may start to discriminate based on the creditworthiness of the underlying borrowers and the geography of where they are located. In an extreme scenario, they may only agree to buy “specified” loan pools from high quality borrowers in areas with deeper housing markets. This would likely shrink the TBA market as we know it now, and would almost assuredly translate to higher rates for borrowers more broadly.11

- How does the Uniform Mortgage-Backed Security (UMBS) work if there is no explicit guarantee?

The UMBS,12 which allows either Fannie or Freddie pools to be delivered into the same TBA contract, works primarily because of the assumption that Fannie and Freddie MBS are entirely fungible. This fungibility only functions now because the government stands behind the loan pools regardless of whether they are Fannie- or Freddie-backed. If there were no explicit guarantee upon release, this fungibility would be in doubt and could return the market to the days of separate Fannie and Freddie TBAs or specified loan pools, as noted above. This could create friction that would almost certainly lead to higher mortgage rates. Additionally, there is the (admittedly wonky) question of whether Freddie would once again pay the Market Adjusted Pricing (MAP) fee should the UMBS no longer exist.

- What would be the impact on Ginnie Mae, which does have an explicit guarantee?

Without an explicit guarantee, we would expect to see some, if not significant, volumes of loans from mortgage originators shift to Ginnie Mae from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. If and when that were to occur, it would 1) call into question the objective of the release, assuming it is to decrease the footprint of Fannie and Freddie, and 2) affect their business models and ultimately their post-release valuations, which are partially based on loan volumes. Indeed, Fitch Ratings recently warned that its current A rating on the GSEs could be lowered if “the GSEs’ post-conservatorship market position erodes.”13

- If agency MBS were viewed by the market as having both credit risk and interest rate risk, how would asset owners treat them in their portfolios?

If the GSEs are released without an explicit guarantee, meaning they suddenly have both interest rate and credit risk, would asset owners—such as public and private pension plans, and sovereign wealth funds—consider agency MBS more like high-quality investment-grade bonds (such as those issued by Apple or Johnson & Johnson) rather than Treasuries, as they do now?

In fact, some more risk-averse investors may be inclined (or required) to significantly scale back their holdings of agency MBS, which could lead to selling or fewer purchases. Either way, given the supply and demand dynamic and the impact on mortgage rates, even incrementally less demand would likely result in upward pressure on mortgage rates.

- How would banking regulators treat Fannie and Freddie MBS if there was not a codified guarantee?

In conservatorship, agency MBS currently enjoy a 20% risk-weighted asset (RWA) calculation under Basel rules and receive Level 2A Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) treatment. In contrast, the debt of investment-grade issuers, including well-capitalized issuers such as Microsoft, is assigned a 100% risk weighting and Level 2C LCR treatment.

Would banking regulators change the capital treatment of agency MBS if there were only an implied guarantee and not a legislated one? The Bank for International Settlements has indicated that any change in the status of conservatorship would prompt a review of the GSEs' capital treatment.14 What would be the implications for current capital holdings at banks, as well as the appetite to buy more?

- What would happen in a recession? Should Fannie and Freddie be released without a codified guarantee, what would happen to mortgage rates in a downturn?

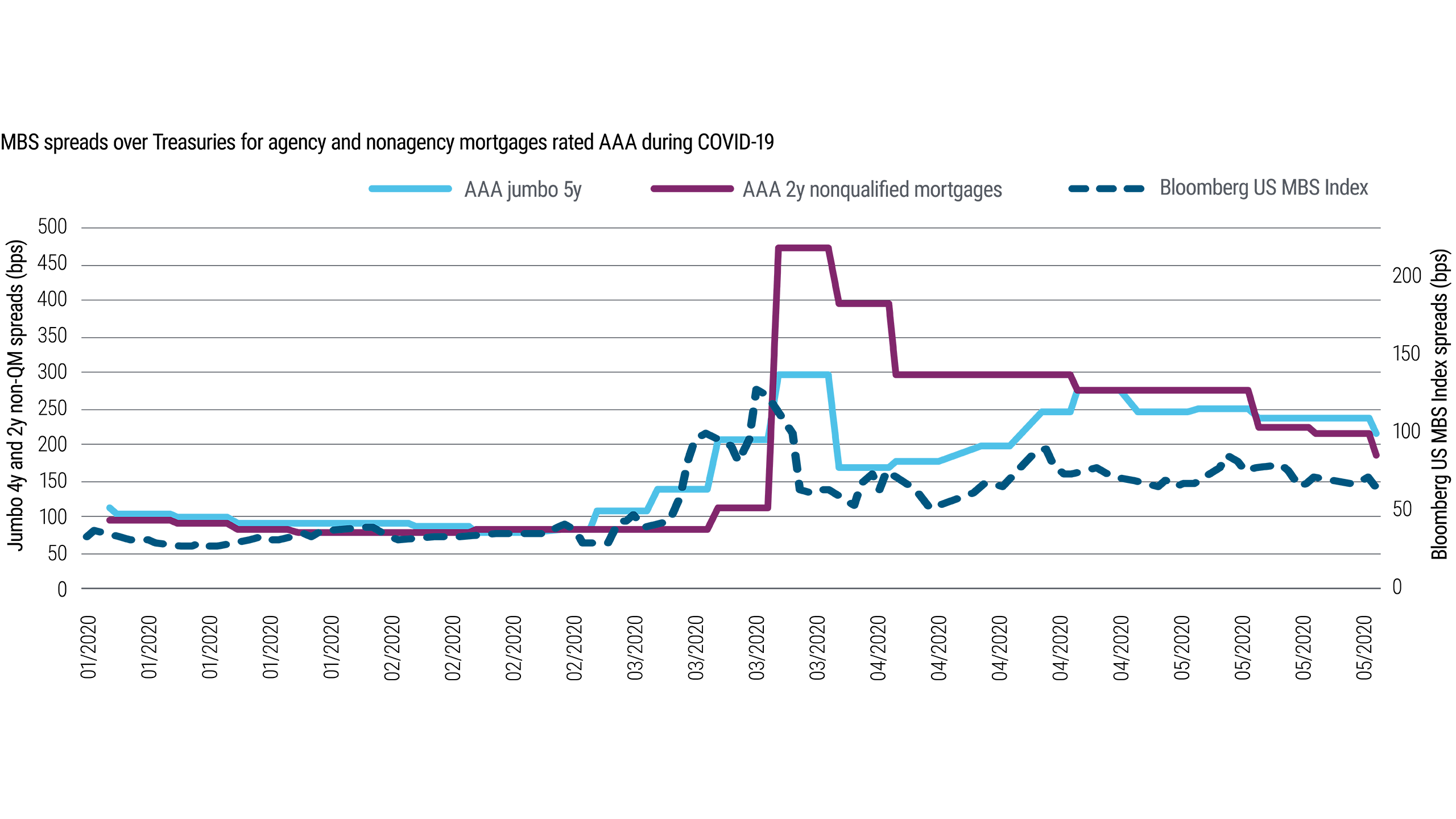

One of the roles the GSEs have played during downturns, including the one induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, has been to provide countercyclical support to the mortgage and housing markets. If agency MBS trade with any credit risk premium—which tends to widen during slowdowns—mortgage rates, all else equal, would increase at a time when policymakers would want them to decrease (which they likely would have otherwise). The starkest recent example occurred during the pandemic, when nonqualified and jumbo mortgages traded higher relative to agency MBS (see Figure 3).

Conclusion: Don’t fix what isn’t broken

While we understand the desire of policymakers to take action on the GSEs, we also believe it is essential that they “do no harm” to the deep, liquid, and well-functioning agency MBS market – particularly when mortgage rates are high and housing affordability is top of mind. If reform is the goal, we believe the FHFA has many tools that would enable reform without congressional action and/or the release of the GSEs, which could nonetheless shrink the government footprint and crowd in private capital.

However, if the decision is ultimately made to privatize the GSEs, we believe that Congress legislating an explicit government guarantee is the only way to ensure that there is no disruption to the agency MBS market broadly, and specifically to the all-important 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. Indeed, doing so could actually have benefits to mortgage rates and to the economy more broadly.

ENDNOTES

- eMBS and PIMCO as of 20 February 2025 Includes all single-family to-be-securitized-eligible mortgage pools outstanding ↩

- Defined as the conforming market. Source: https://www.nar.realtor/fannie-mae-freddie-mac-gses ↩

- https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/10/25/a-look-at-the-state-of-affordable-housing-in-the-us/ ↩

- https://www.fanniemae.com/research-and-insights/perspectives/look-back-10-years-credit-risk-transfer ↩

- https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/senator-toomey-process-exiting-gse-conservatorship-not-so-simple ↩

- Among other things, the PSPA amendment limited Fannie and Freddie’s purchase of second homes and investment properties to 7% of total acquisitions; https://www.fhfa.gov/news/news-release/fhfa-and-treasury-allow-fannie-mae-and-freddie-mac-to-continue-to-retain-earnings https://www.bankingjournal.aba.com/2025/01/agencies-eliminate-pspa-restrictions-on-fannie-mae-freddie-mac-conservatorships/ ↩

- https://www.markets.jpmorgan.com/research/email/scx/svp26u7t/GPS-4893587-0/ff8af1a8-30f5-4b5d-b923-174a4520d469 ↩

- https://www.bis.org/basel_framework/ ↩

- https://www.home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2767 ↩

- https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/senator-toomey-process-exiting-gse-conservatorship-not-so-simple ↩

- As discussed at length in Jim Parrott and Mark Zandi’s January 2025 piece:

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2025-01/Fannie%2C%20Freddie%20%26%20Implicit%20Guarantee%20-%20Parrott%20%26%20Zandi%20-%20January%2014%2C%202025.pdf ↩

- https://www.fhfaoig.gov/sites/default/files/WPR-2020-001.pdf ↩

- https://www.fitchratings.com/research/non-bank-financial-institutions/fannie-freddie-conservatorship-exit-would-not-be-immediate-ratings-catalyst-08-01-2025 ↩

- "While the [Basel] Committee [on Banking Supervision] notes the uncertainty regarding any future changes to the legal or regulatory structure for these entities, it recommends that the treatment of securities issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as Level 2A HQLA be reviewed should the conservatorship end or their legal status otherwise materially change.” See https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d409.pdf. ↩