China’s Reopening, Trade Tensions Create Opportunities Within Emerging Markets

- Asian countries such as Thailand that are closely linked to China’s service sector may stand to benefit the most over the cyclical horizon as tourism recovers.

- The trade rift between China and the U.S. could accelerate nearshoring policies, with potential beneficiaries including Mexico, India, and Malaysia.

- EM debt continues to offer diversification benefits and attractive yields compared with allocations to core markets.

The relaxation of zero-COVID-19 policies bodes well for China’s economy this year, bolstering an already constructive global macroeconomic backdrop for emerging markets (EM). Growth in developed markets (DM) has been more resilient than expected, though recent stress in the U.S. and European banking sectors may increase the risk of a deeper recession. In addition, global headline inflation looks to have peaked, and the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) may be nearing the end of its policy tightening cycle.

Asian economies with large exposures to China’s consumer and service sectors may stand to gain the most. Commodity exporting countries are also likely to benefit, but the effects may be more modest and varied compared with previous cycles. Oil could see a minor boost in demand – at a time when OPEC plans to cut production – from China’s transportation sector, while industrial materials such as aluminum and steel that are heavily used in construction are unlikely to see strong tailwinds.

Even as EM stands to broadly benefit from China’s recovery, geopolitical and trade frictions between China and the U.S. are likely to persist. This will have varied impacts across EM countries as global trade relationships are realigned.

Pent-up demand set to drive China’s growth

China’s lifting of pandemic controls, accompanied by its support measures for the housing sector, are signals that the government has shifted its focus back to the economy. Historically, China’s economic cycles have been mostly policy-driven, and we expect a strong growth rebound in the coming months. We forecast 2023 growth at about 5.5% (with upside potential), with China being one of the few large economies where 2023 growth exceeds 2022 levels.

The recovery in this cycle would not be business as usual, as China’s growth drivers should shift from investment to consumption. We expect strong momentum in travel, tourism, entertainment, business events, and catering supported by excess household savings.

As global demand abates amid the widespread risk of recession, China’s exports will likely slow. Imports should bounce back as domestic demand recovers, and outbound overseas tourism will likely rise. This would result in a narrower goods trade surplus and a surging service deficit. Importantly, the sustainability of China’s recovery will depend on the country’s policy adjustments and the stability of the global economy.

EM poised to benefit from China’s cyclical momentum

Since the global financial crisis of 2008, China’s impact on EM growth has increased and overtaken that of the U.S. and the eurozone. A 1 percentage point increase in China growth raises EM growth by 0.2 to 0.4 percentage points, according to data from the International Monetary Fund and J.P. Morgan. While this may be an overestimate for this cycle, given China’s lower marginal propensity to consume EM goods in lieu of services, it should nevertheless be supportive for EM growth.

A closer look at the beneficiaries of Chinese growth suggests three main groups of countries:

- Asian economies with large exposures to China’s consumer and service sectors stand to benefit the most. January 2023 data from online travel company Ctrip suggest the top 10 most popular destinations for Chinese tourists are Australia, Thailand, Japan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, the U.S., Singapore, the U.K., Macau, and Indonesia. We are particularly constructive on the gaming industry in Macau.

- Commodity exporters, such as certain Latin American countries, are likely to benefit more modestly via the broader price impact on commodity markets as opposed to the direct demand from China. This channel is likely to be less significant than in the previous cycles as the recovery would be driven mainly by consumption, which is less commodity-intensive than the investment that used to drive China’s growth.

- EM more broadly should benefit from the indirect impact on global growth and market sentiment, with the potential to offset the cyclical drag from an expected slowdown in DM (for more on the global economy, read our Cyclical Outlook, “Fractured Markets, Strong Bonds”).

Trade relationships realign

While China’s growth looks poised to rebound, geopolitical and trade frictions between China and the U.S. are likely to persist, with important implications across EM. Broad shifts in supply chains appear to be underway, albeit gradually.

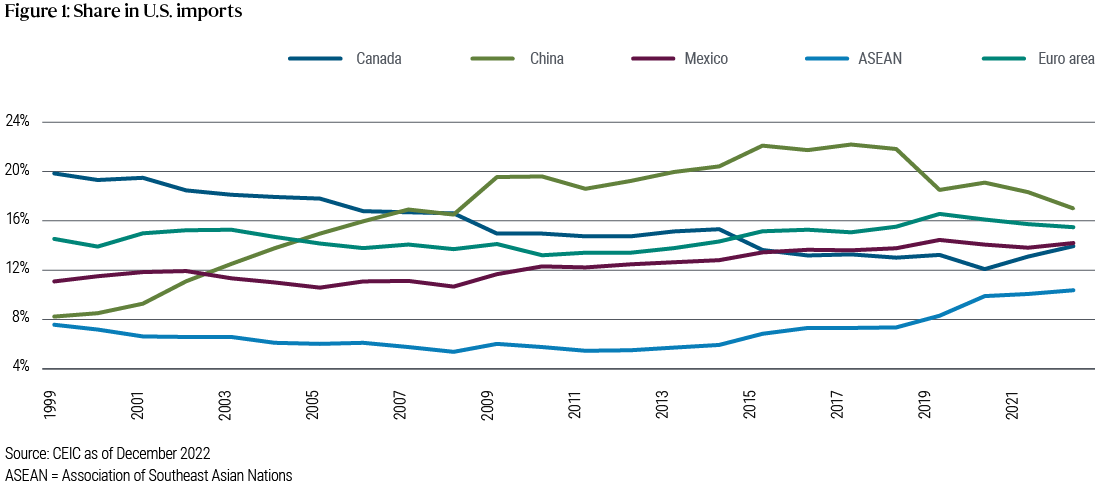

Since 2019, Asia (excluding China), Mexico, and Canada have expanded their contributions to U.S. total imports, while China’s share continues to drop, suggesting nearshoring is underway (see Figure 1). This also may have been in part due to a redirecting of Chinese imports via Asia, where, for example, Chinese exports have increased.

That trend may be stymied as the U.S. strategy has shifted from bilateral competition to more extensive restrictions on trade via third parties. As a result, Asian economies may increasingly look to be neutral.

Moreover, as outbound investment to China could be the next target for U.S. restrictions, U.S. multinational corporations are already looking to relocate supply chains out of China, particularly for U.S.-destined and specific tech sector exports. Countries such as Malaysia and India are potentially poised to benefit from these longer-term trends toward tech nearshoring by the U.S. Both countries already have competitive tech sectors, with skilled human capital and infrastructure to expand further.

Of the countries positioned to benefit from nearshoring, Mexico stands out for its strong trade, financial, and economic linkages with the U.S. The USMCA trade agreement implies lower direct costs from trade tariffs, while indirect costs are lower and there are clear resolution mechanisms in the event of disputes. Unit labor costs in Mexico are now lower than in China, while the country’s proximity to the U.S. can reduce transportation costs.

Mexico’s market share in U.S. motor vehicle imports has grown by 3.9% since 2018. Mexico’s foreign direct investment (FDI) data also point to an increase in manufacturing FDI since 2019.

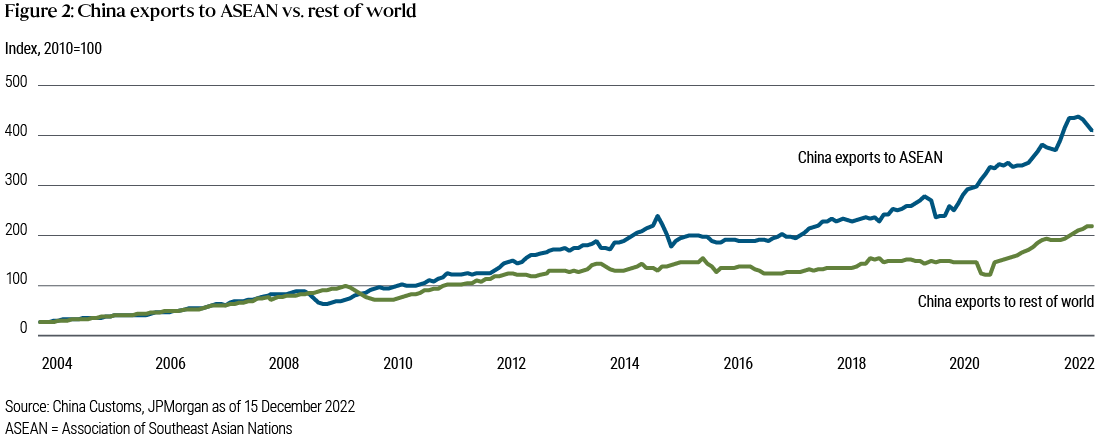

Medium-term trends in China’s supply chain are affecting EM in different ways. These include a shifting of downstream production to lower-cost regional producers such as Vietnam and Bangladesh. China’s outward direct investment to the region has increased sharply, as have China’s exports to the region compared with the rest of the world (see Figure 2). On the upstream side, particularly in tech-related trade flows, Taiwan has gained share over Korea and Japan, potentially due to geopolitics and cost considerations.

In the long run, we believe these trends will continue. Chinese exporters will likely try to explore new markets in the developing world and EM, seeking to mitigate the impact of U.S. restrictions.

That said, we believe that with its significant trade imbalance with the U.S., and a wide gap in technology and financial markets, China is unlikely to take material retaliation measures against the U.S. Instead, it will likely continue to boost domestic demand, along with research and development, to reduce reliance on foreign markets and technology. Also, similar to the U.S., China likely will continue to expand its global influence and seek cooperation with possible allies.

For EM, this means countries will look to thread the needle between U.S. and China strategies. Some countries will naturally benefit from this trend, while others will look to remain geopolitically neutral. The result is likely to be a more differentiated and multipolar EM landscape.

Investment implications

Our cyclical outlook for EM is constructive, as China’s reopening disproportionately boosts EM and with the Fed appearing near the end of its rate-hiking cycle. EM’s diversification benefits and yield advantage compared with core markets should persist.

We believe one way to seek opportunities resulting from the effects of China’s reopening on EM is considering Asia currencies such as the Thai baht and Korean won. PIMCO believes the U.S. dollar, which has depreciated since hitting a 20-year peak last September, is likely to fall further in 2023 as inflation recedes, recession risks rise, and other shocks abate.

Select exposures in EM local debt (denominated in local currencies), such as in Brazil and Mexico, can offer high relative real yields, which appear attractive given the phase of the current economic and rate cycle.

We also see opportunities in hard-currency debt of select high quality countries that may benefit from nearshoring trends, as well as those countries that may be less exposed to related downside risks.

Featured Participants

Disclosures

All investments contain risk and may lose value. Investing in the bond market is subject to risks, including market, interest rate, issuer, credit, inflation risk, and liquidity risk. The value of most bonds and bond strategies are impacted by changes in interest rates. Bonds and bond strategies with longer durations tend to be more sensitive and volatile than those with shorter durations; bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise, and low interest rate environments increase this risk. Reductions in bond counterparty capacity may contribute to decreased market liquidity and increased price volatility. Bond investments may be worth more or less than the original cost when redeemed. Commodities contain heightened risk, including market, political, regulatory and natural conditions, and may not be appropriate for all investors. Currency rates may fluctuate significantly over short periods of time and may reduce the returns of a portfolio. Investing in foreign-denominated and/or -domiciled securities may involve heightened risk due to currency fluctuations, and economic and political risks, which may be enhanced in emerging markets. Diversification does not ensure against loss.

Forecasts, estimates and certain information contained herein are based upon proprietary research and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. There is no guarantee that results will be achieved.

Statements concerning financial market trends or portfolio strategies are based on current market conditions, which will fluctuate. There is no guarantee that these investment strategies will work under all market conditions or are appropriate for all investors and each investor should evaluate their ability to invest for the long term, especially during periods of downturn in the market. Outlook and strategies are subject to change without notice.

PIMCO as a general matter provides services to qualified institutions, financial intermediaries and institutional investors. Individual investors should contact their own financial professional to determine the most appropriate investment options for their financial situation. This material contains the opinions of the manager and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This material has been distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission. PIMCO is a trademark of Allianz Asset Management of America LLC in the United States and throughout the world. ©2023, PIMCO.

CMR2023-0412-2836488