China’s ability to sustain fairly robust economic growth despite a massive property sector downturn is now facing new tests as global trade barriers rise, and domestic demand shows fresh signs of weakness. Looking ahead, China’s excess industrial capacity and mounting inventories are likely to intensify deflationary pressures – forcing policymakers either to further stimulate domestic consumption or to tolerate slower growth. The readout from China’s recent fourth plenum acknowledges this economic reality. However, how quickly China can shift its growth model inward remains a key question.

Why China’s property market downturn didn’t wreck its economy

China’s recent property sector bust after a period of overbuilding could be fairly compared with Japan’s experience in the 1990s and the U.S. experience in 2008. Japan’s real residential investment contracted about 40% in the eight years following its 1990 peak, leading to a decade of economic stagnation, while similar activity in the U.S. contracted about 60% in the four years after its 2007 peak and set off the global financial crisis (according to official statistics in both the U.S. and Japan).

In many ways, China’s economy seems well on its way to match these episodes. After peaking in early 2021, nominal residential construction activity is down roughly 40%, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). That’s about 30% in real terms given the roughly 10% price depreciation of China’s building materials production price index. We expect China’s property sector will continue to contract: Many “zombie” developers still need restructuring, and much property remains vacant.

However, the similarities between China’s experience and those of Japan and the U.S. largely end there. Despite a similar scale of property sector decline, China’s broader economy still managed to grow roughly 4.5%–5% per year, according to NBS, and its closed capital accounting limited spillover into global financial markets.

How did this happen? Central government directives stimulated offsetting growth in other sectors while limiting contagion from the housing sector. Specifically, policymakers have focused on increasing manufacturing capacity (especially electric vehicles, batteries, and solar cells), infrastructure investment, and export growth. At the same time, they have aimed to stabilize the property sector without reflating prices – akin to spreading losses slowly over time, as opposed to a quick forced deleveraging.

In 2024, this policy largely worked. Materials originally manufactured for the Chinese property sector – such as steel and concrete – were instead exported to many emerging markets (EM), while Chinese green energy goods pursued European markets to increase global market share.

Indeed, despite the property sector contracting in 2024 to 6% of China’s GDP instead of 10%, net exports and investment accounted for roughly 2.3 percentage points (ppts) and 1.3 ppts of real GDP growth in 2024, with domestic consumption filling in the rest. Chinese export prices fell relative to those of the rest of the world as Chinese industry scaled up and cut prices to drive export volumes while fierce internal competition shrunk margins and kept profits low.

New risks to China’s growth strategy

China’s supply- and export-driven growth model has helped at least delay the fallout of the property sector bust despite only targeted fiscal supports – but that model now faces limits.

In response to China’s aggressive price discounting, many EM economies have erected higher tariff and trade barriers on Chinese goods imports. Europe has initiated investigations into Chinese product dumping and may increase the use of quotas. The U.S. has raised tariffs on all trading partners, but especially on Chinese goods, which has limited the ability of Chinese producers to access the U.S. market at lower tariff rates through “connector” countries for final stages of production. Although markets have shown signs of optimism for U.S.–China trade negotiations ahead of the countries’ presidents meeting this week, the relationship between these two major economies will likely remain volatile.

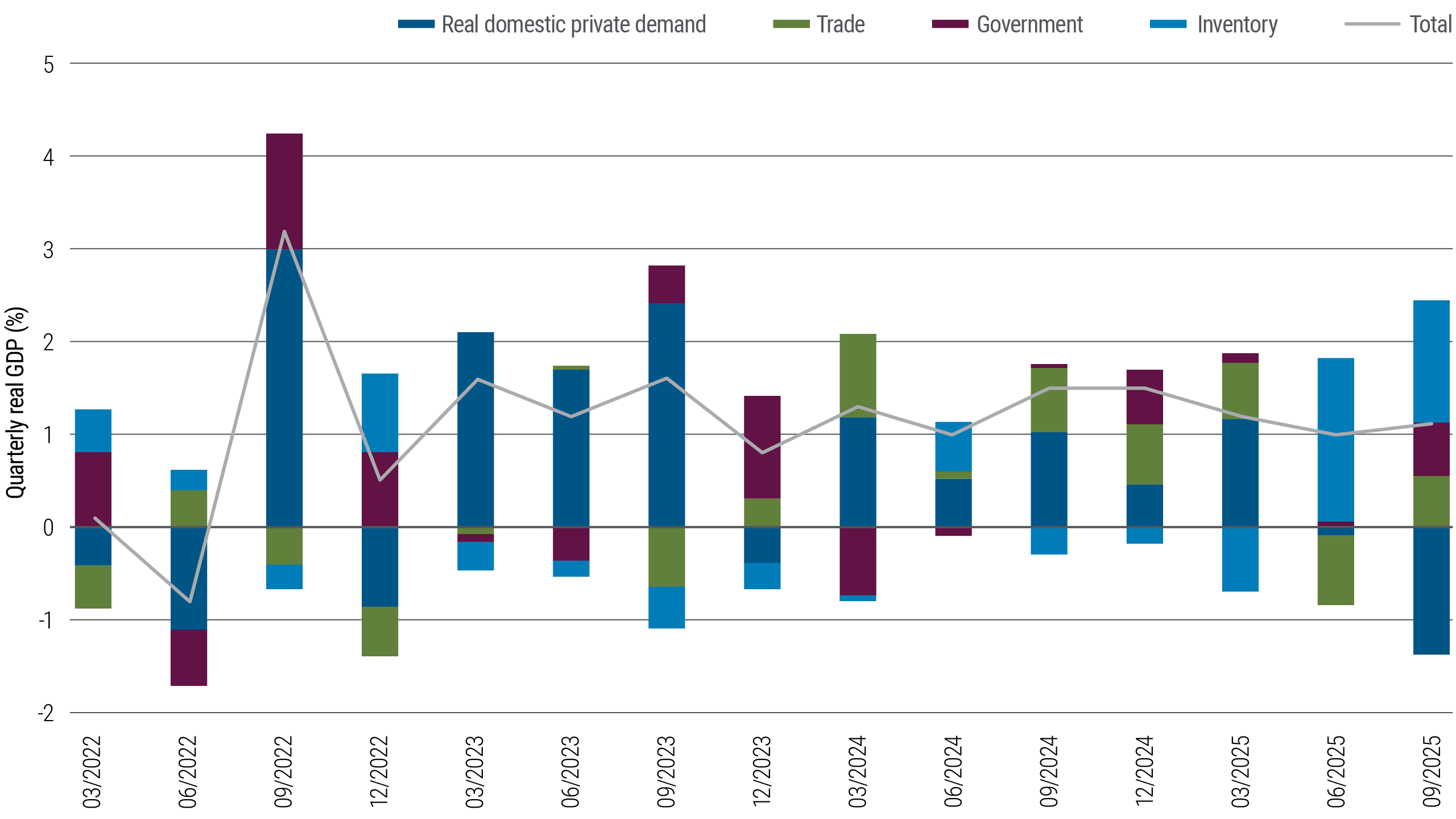

China’s third-quarter real GDP data are consistent with these trade challenges resurfacing, after front-loading ahead of U.S. tariffs stimulated Chinese activity in the first half of 2025. Although the headline year-over-year and year-to-date real GDP figures were better than many expected, decomposing the quarterly growth rates by GDP expenditure categories (e.g., consumption, investment, trade) reveals weakness under the surface.

Private domestic demand (i.e., private consumption plus investment) isn’t specifically reported in the official GDP figures, but we can calculate it by combining reported figures on fixed asset investment and the NBS’s quarterly Households’ Income, Consumer Expenditure and Living Conditions Surveys with the official GDP data. The analysis is eye-opening: Private domestic demand saw its largest quarterly contraction since the pandemic – the contraction in fixed asset investment has spread from the property sector to manufacturing and infrastructure investment. (Even growth in state-owned enterprise investment, which has been remarkably stable over the last several years, has fallen recently.)

Trade was a positive small contribution to GDP in the third quarter, but this followed a negative contribution in the second quarter after U.S. tariff announcements (which were later moderated) temporarily disrupted trade flows. Perhaps most concerning, inventory accumulation – which our calculations suggest accounted for the bulk of the positive GDP surprise in the third quarter – came on the heels of a large accumulation in the second quarter. For a detailed breakdown, see Figure 1.

This GDP decomposition corroborates our measure of China’s trade and inventories, aggregated from China’s trade partners, and its own detailed industry data. Indeed, according to trade partner reports, Chinese export growth has slowed dramatically since last year. It’s likely closer to flat nominally and up only slightly in inflation-adjusted terms, while inventory-to-sales ratios calculated from detailed industry data have continued to tick higher.

Overall, the latest data suggest that despite stronger-than-expected reported real GDP growth, China’s domestic conditions have weakened recently while trade growth is slowing (trade with Africa is an exception). Despite these challenges, Chinese production has continued at a robust pace, with both raw materials and finished goods inventories accumulating.

Takeaways for China’s outlook: domestic challenges and trade barriers

Looking ahead, inventories can’t keep piling up forever if China wants to counter deflationary trends and maintain a stable economy. China’s policymakers have recently emphasized an “anti-involution” campaign: a nuanced approach to counter the intense competition that shrunk profit margins and to emphasize higher-quality growth and greater profitability, with a goal of reducing deflationary pressures.

However, unless Chinese policymakers are willing to more forcefully stimulate domestic demand, or tolerate slower production growth, Chinese products would need to continue to be exported at further price discounts to clear the inventory levels.

Fiscal stimulus is coming in more forcefully. However, we see signs of infrastructure increasing, which raises questions around China’s commitment to move away from production and export-led growth. The smaller, more targeted fiscal supports aimed at households, including credits for upgrading household equipment to newer, more energy-efficient models, and efforts to engineer a greater wealth effect through stimulating equity price gains, don’t appear to be working. The increase in local government bond issuance has been absorbed by still-high household saving rates, keeping both household consumption and local government bond yields incredibly low.

Overall, China’s economy must deal with excess economic capacity by stimulating domestic private activity or set growth targets at lower levels that strictly contain production. Until China sees more progress in these efforts, its deflationary domestic conditions will very likely continue to spill over into the global economy, with countries that have still-low trade barriers most affected.