The Federal Reserve is poised to cut interest rates this week, potentially offering some relief to prospective U.S. homebuyers hamstrung by elevated mortgage rates. But rate cuts might not be the Fed’s most direct path to supporting housing. For a more targeted approach, the Fed may just need to rethink its playbook for the mortgage bonds on its balance sheet.

Since 2022, when it started hiking rates, the Fed has also been steadily shrinking its bond holdings. It has allowed principal and interest payments on mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to roll off its balance sheet without reinvestment, a process known as quantitative tightening (QT).

QT is a reversal of the quantitative easing (QE) bond-buying policy the Fed used to support the financial system after the global financial crisis and the pandemic. The Fed bought its first mortgage bond in 2009, so managing its MBS holdings has been an active policy tool for 16 years.

QT can shift the supply–demand balance in the MBS market, with significant knock-on effects for mortgage rates. Agency MBS continue to trade at unusually wide spreads as the Fed passively reduces its holdings and with banks comparatively inactive in the market.

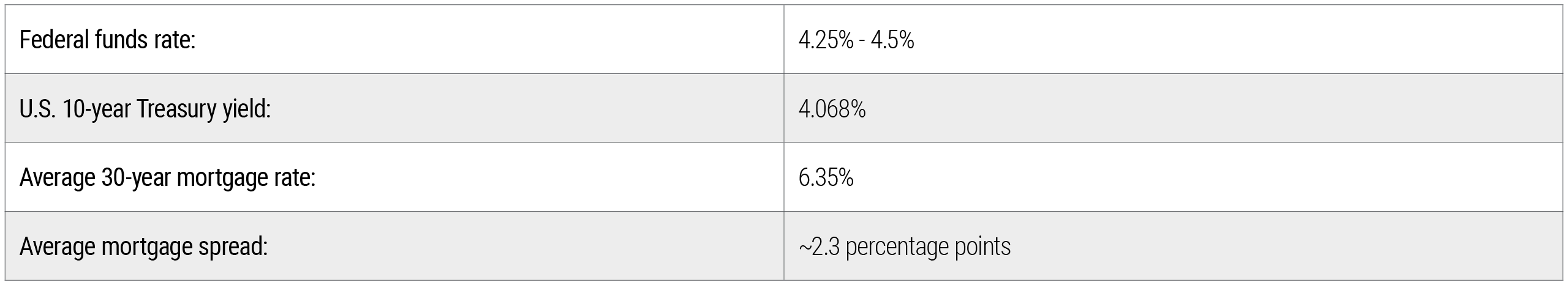

Although the Fed’s policy rate has a broad influence as a borrowing gauge, the 10-year Treasury yield is a more important benchmark for mortgage rates, and that’s set by the bond market. Meanwhile, mortgage spreads – the gap between Treasury yields and mortgage rates (see Figure 1) – are also determined by market forces, and those remain near historically wide levels.

A more direct approach

Wide mortgage spreads present a problem for monetary policy transmission. The Fed’s policy rate may be heading down toward 4%, but mortgage rates remain north of 6%.

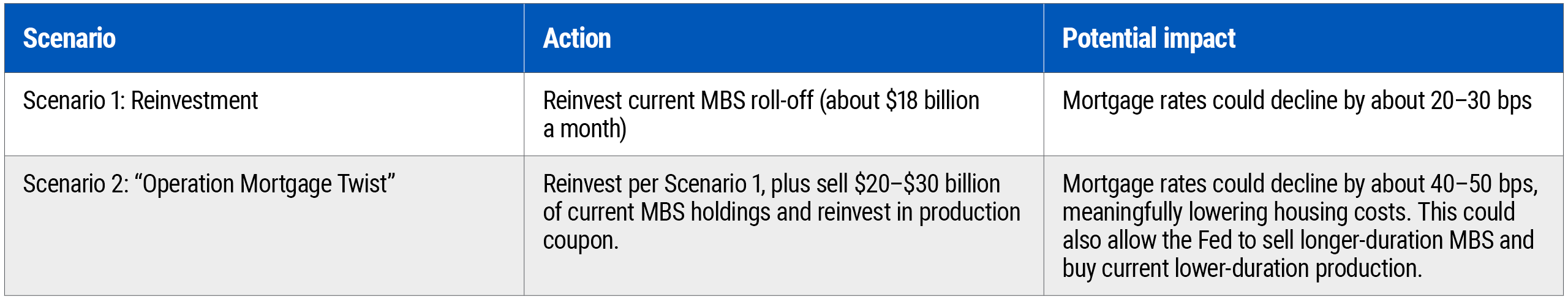

What if the Fed simply stopped shrinking its MBS holdings? Reinvesting the roughly $18 billion in current monthly roll-off into new mortgage securities could compress mortgage spreads by 20 to 30 basis points (bps), in our view. That wouldn’t be restarting QE – it would just keep MBS holdings steady. And it could deliver as much bang for the buck as a 100-bp cut to the federal funds rate, which is what has historically been needed to achieve a similar drop in mortgage rates.

An even more aggressive option: Sell $20–$30 billion of legacy MBS each month and reinvest proceeds into current securities (see Figure 2). We estimate that could push mortgage rates down by 40 to 50 bps.

It could also meaningfully shorten the duration – a gauge of interest-rate risk – of the Fed’s balance sheet. That could be a win for policymakers worried about the effect of elevated federal debts and deficits on U.S. borrowing costs.

Affordability remains challenged

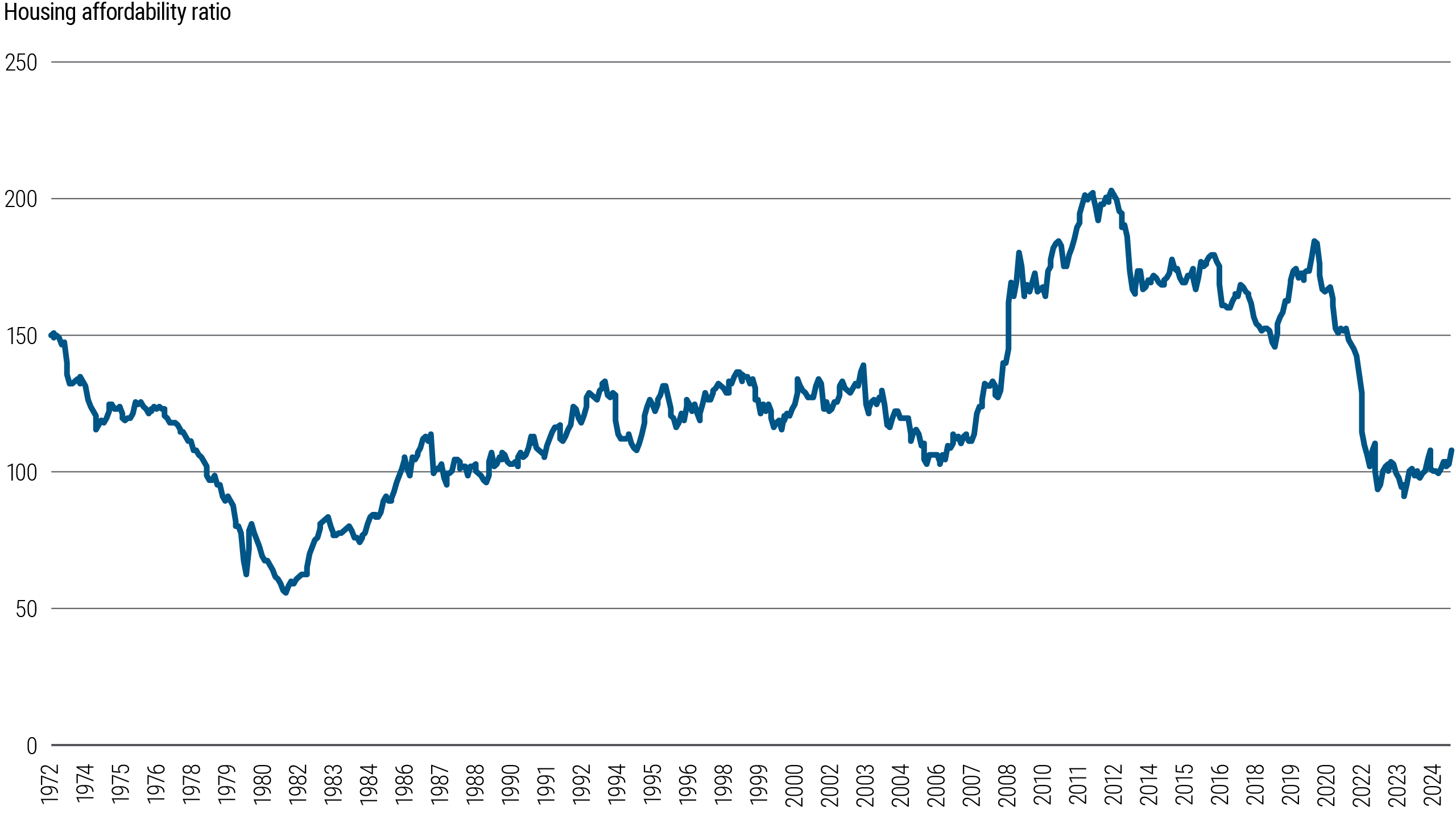

To be sure, ending MBS runoff wouldn’t be a cure-all for the U.S. housing market. Average U.S. home prices have ticked lower in recent months, according to Federal Housing Finance Agency data, but by some measures housing is as unaffordable as it has been in more than three decades (see Figure 3). A lack of inventory could continue to support house prices.

But with officials now looking to reduce interest rates, it’s worth examining the relative effectiveness of the Fed’s monetary tools at transmitting policy into the U.S. economy. In a cycle where interest rate policy is politically fraught and inflation remains sticky, the Fed may find that the most effective easing tool is already hiding in plain sight.

If the Fed continues its current approach, expect mortgage rates to remain elevated through 2026, making homeownership a luxury good reserved for the wealthy. The question isn't whether Fed officials can improve this situation – it's whether they will.