As a major investor in global bond markets, PIMCO welcomes the recent focus of European policymakers on securitisation. Structuring or securitising various types of debt offers vital financing beyond traditional banking channels, supporting Europe’s growth, resilience, and competitiveness, including key objectives such as energy transition and increased defense production.

However, we believe reforms should be holistic and comprehensive, rather than merely incremental. Specifically, we believe it is crucial that policies help to unlock pent-up, yet largely untapped, demand from UCITS (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) funds, which are highly regulated investment vehicles.

What is securitisation, and why is it important?

Simply put, securitisation involves packaging loans made by banks or other financial institutions to various borrowers, and selling them to investors. The types of loans form an alphabet soup of acronyms – including ABS or asset-backed securities; RMBS, also known as residential mortgage-backed securities; and CLOs or Collateralized Loan Obligations. Borrowers range from individuals buying homes or cars to corporations building airplanes or factories.

Securitisation is a win for all parties: It enables banks to free up balance sheet capacity to make additional loans; it deepens and diversifies funding sources, making the economy less reliant on banks, which helps to reduce systemic risk; and it gives retirees and other investors access to a secure, income-generating asset class that would otherwise remain on a bank’s balance sheet. Additionally, securitisation offers a feature that no other capital market instrument provides: customised, very flexible solutions for both sellers and buyers. Originators and sellers, typically banks, can carve out collateral that best fits their needs and efficiently tranche risk, fostering a diverse investor ecosystem across various risk/return profiles.

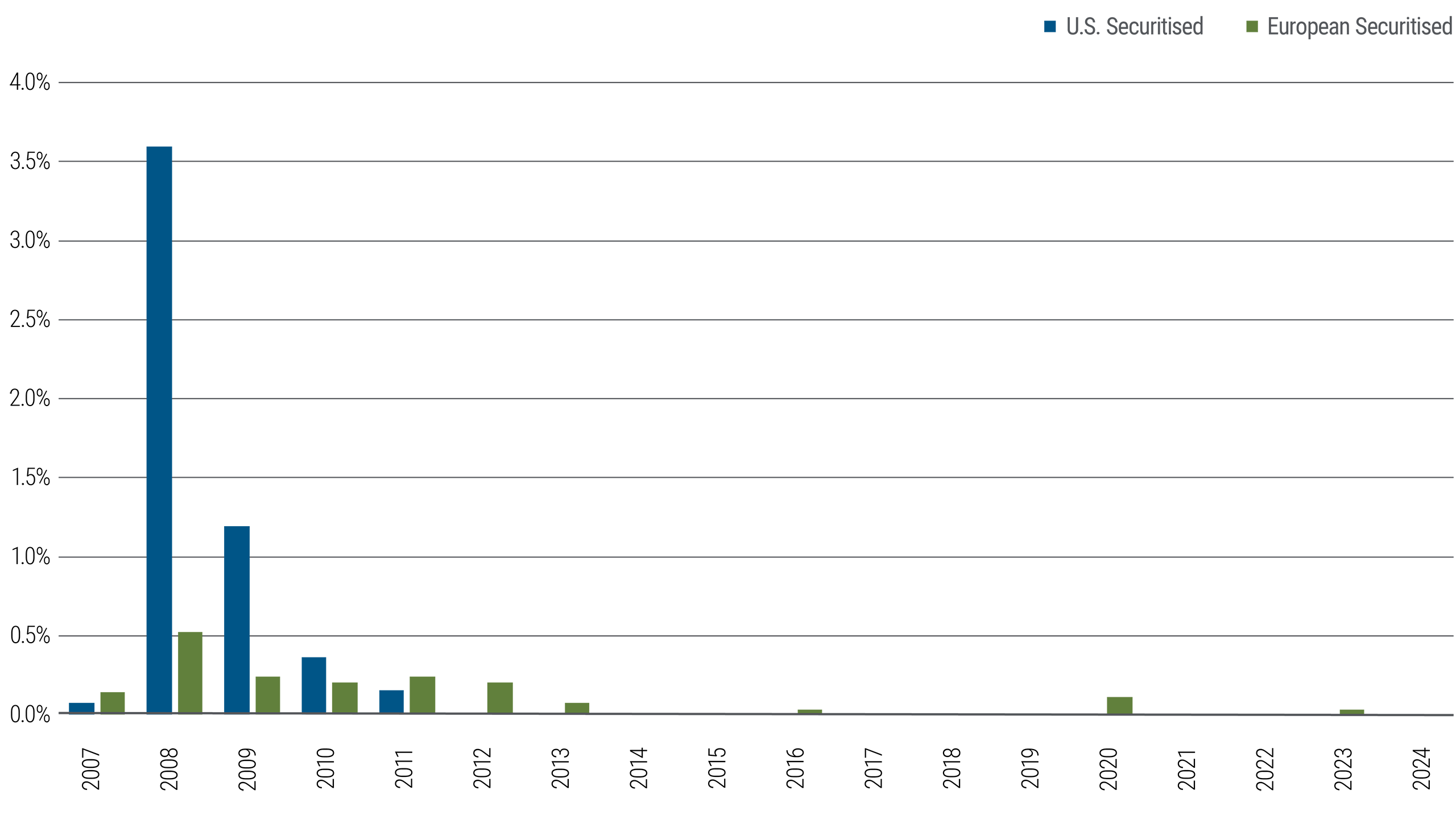

The global financial crisis (GFC) highlighted the risks of securitisation. When lending standards declined and significant leverage was allowed, defaults occurred, especially in the U.S. However, post-GFC regulatory reforms in both the U.S. and the EU have made senior tranches of today’s securitisations among the least risky securities in the marketplace, while still offering attractive return potential. These regulations have curbed high-risk lending, compelled banks to hold some exposure to their securitisations, halted excessive leverage through layering, and significantly improved transparency. This has produced very low defaults in both Europe and the U.S. (see Figure 1).

Why do investors like securitisations?

Securitisations offer several potential benefits for investors, especially retail clients, that other investments might not:

1) Diversification: Securitisations are well-diversified across thousands of loans, with investor-friendly, conservative structures. Recent reforms have further enhanced their safety, reducing the risk of absolute and relative defaults.

2) Tailored income: Securitisations offer tailored risk/return profiles that generate income and amortize over time. As interest and principal payments from underlying borrowers flow to the investor holding the securitisation, this structure is particularly beneficial for retirees who depend on a fixed income.

3) High quality: Securitisations are generally high quality because they are backed by loans on tangible assets, such as houses, cars, and equipment. Supported by thousands of well underwritten loans, securitisations are less vulnerable to the default of an individual borrower. In contrast, a corporate bond issued by one issuer is “unsecured,” (i.e., lacking in collateral support), as is the case with Glencore, Telecom Italia, Ford, GM, or fraudulent entities like Wirecard.

The need for a European focus

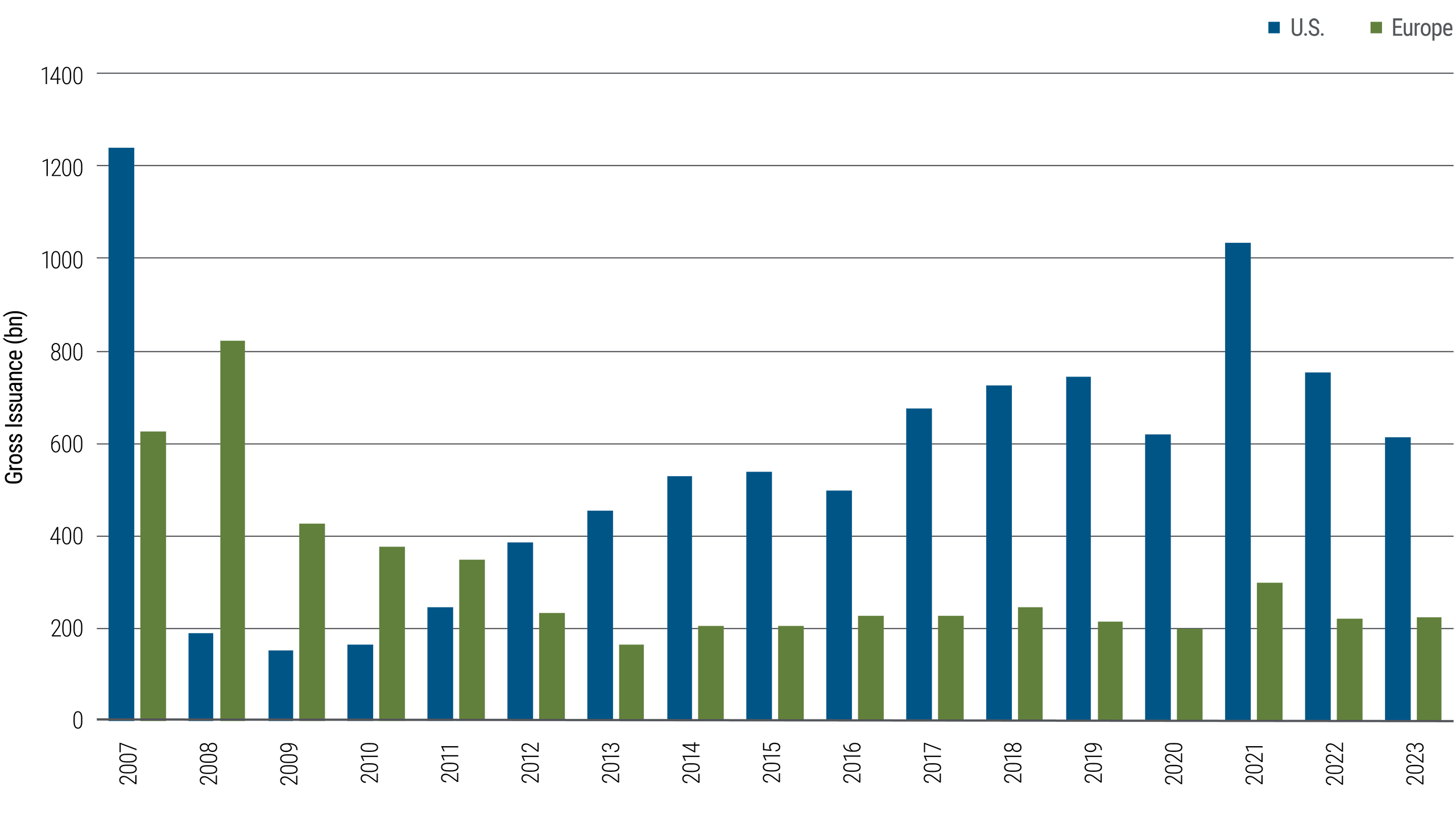

The securitisation market in Europe remains moribund and significantly smaller than its U.S. counterpart (see Figure 2). In Europe, securitisations account for just 0.3% of GDP, compared to approximately 4% in the U.S.Footnote1

As highlighted in a recent report by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi,Footnote2 the EU has overly relied on bank financing, which faces constraints that limit broader European economic growth. Securitisation holds the key to unlocking the much-needed credit channel and creating deeper capital markets in Europe.

In our 2024 Economic and Market Commentary, ”Navigating the Challenges EU Securitisation Regulation and Its Effects on Investors and Markets,” we noted that while many regulations governing securitisations are well-intentioned, they have had unintended consequences that arguably impede market growth, vitality, and liquidity, thereby hampering overall growth in the European economy. We hope that policymakers use this opportunity to reconsider some of these longstanding rules.

What is essential to unlock more growth? Do not double-down on failed strategies of the past

The European Commission has primarily focused on unlocking the supply of securitisations by reducing “red tape” to stimulate market growth. While boosting supply is essential, it’s equally important to focus on demand – specifically, identifying who will purchase securitisations as production increases.

Policymakers have focused on driving demand from banks and insurance companies, yet this strategy has been tried before. The 2017 introduction of high-quality, STS-labelled (Simple, Transparent and Standardized) securitisations in The European Union, was aimed at encouraging these institutions to buy more securitisations by offering better capital requirements. However this innovation, which became effective in 2019, did not lead to a significant increase in demand or market growth.

Relying solely on banks and insurance companies may not only fail to produce the desired growth in securitisations but also introduce cyclical economic and financial risks. History shows that over-dependence on these traditional financing sources can weaken the overall financial system, especially during challenging economic times, and can result in boom-and-bust cycles, replete with credit crunches. This makes it harder for businesses and individuals to access the financing they need and can hinder economic growth and innovation, broadly weakening the strength of the economy.

If European policymakers are committed to increasing securitisation activity as a lynchpin of future European economic growth and deepening European capital markets, we believe they must go beyond relying on banks and insurers as sources of demand. Instead, in our view, they could consider expanding and diversifying into other pools of capital, such as highly regulated, unleveraged, European UCITS funds. The current consultation on Integration of EU Capital Markets, which addresses some of the UCITS hurdles to invest in securitisations, is a promising step towards a more robust and better diversified economy.

The U.S. shows how vital this source of investor demand can be

European policymakers need only to look across the pond to see the potential benefits of allowing UCITS funds greater exposure to securitisations. In the U.S., ‘40 Act funds, the equivalent of UCITS, are among the largest investors in securitisations. They are attracted by the consistent, reliable income, high liquidity, and diversified collateral, with clear payment characteristics that securitisations potentially offer. Like UCITS funds, ‘40 Act mutual funds have strict concentration, liquidity, and leverage limits to mitigate risks for investors.

Europe is different

In Europe, however, it is a different story. Despite pent-up demand for securitisations among UCITS funds, these funds are constrained by a technical rule from the 1985 Directive that limits their ability to purchase securitisations. This rule, known as Article 56.2 (b), predates the first European securitisation by two years and imposes a 10% “acquisition” limit of outstanding issuance at time of purchase for a security in a “single issuing body.” The rule, as widely understood,Footnote3 was originally intended to prevent an investor from acquiring a large ownership percentage and exercising influence over the management of an issuing body (e.g., a company), as stated in Article 56.1. While EU securitisations did not exist when this rule was adopted, the prevailing norm is that securitized debt remains subject to this 10% acquisition limit.

What is the problem?

The 10% acquisition limit is not necessarily a problem for UCITS buyers of corporate debt, as a company’s outstanding debt is often in the billions to hundreds of billions of dollars. For example, the average investment grade debt issuance for an AA-rated company is around €7 billion, which allows UCITS funds to buy multiple billions of debt issuance in any one company (depending on the size of the fund).

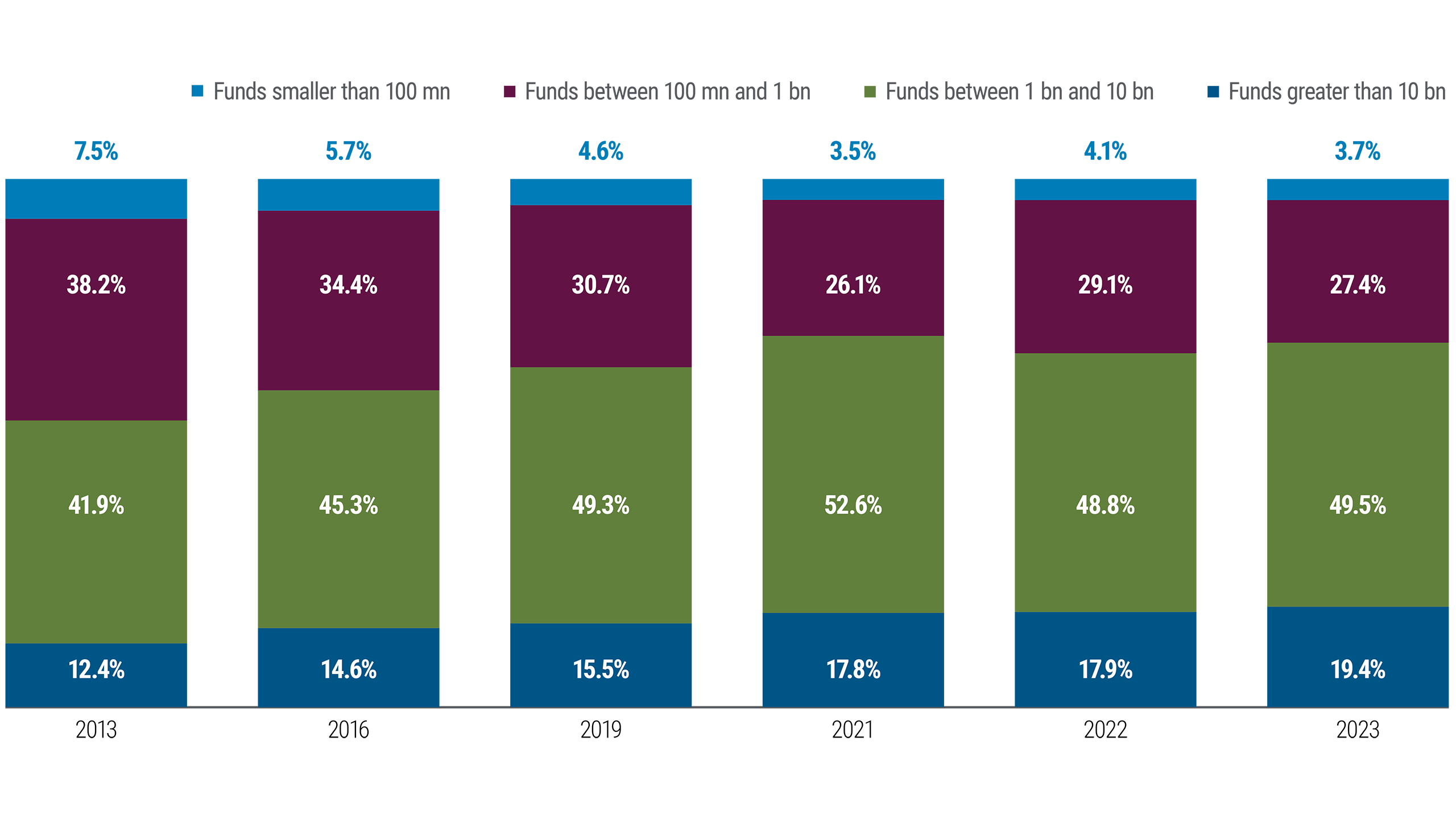

Securitisations, given their bespoke, standalone nature, are significantly smaller, with the average size of European securitisation deal being just ~€300 millionFootnote4. This means that under the acquisition limit, a UCITS fund is limited to purchasing only about €30 million. This is especially small given that the majority of UCITS funds are larger than €1 billion, if not considerably larger (see Figure 3). The growth of the UCITS platform and the size of UCITS funds over the years have only exacerbated this issue, as funds have grown while securitisation deals have remained small.

Because UCITS fund investors cannot gain sufficient exposure to securitisations, fund managers like PIMCO often have to turn to other credit sources, such as unsecured corporate bonds, which are not limited by the acquisition limit. This situation is unfortunate for fund managers, who must take on more corporate risk than desired. It is also disadvantageous for end-investors, such as retirees or savers, who miss out on the diversification and income potential of this attractive and highly regulated asset class.

What changes should be made?

We believe a helpful policy change would be to clarify the definition of “single issuing body” and exclude securitisations from the acquisition limit altogether. This is because

- The 1985 rule was never intended to address securitisations.

- Debt, unlike equity, does not allow for investors to exert control over a securitisation, which was the original purpose of the acquisition limit.

- There is an ongoing legal debate about whether a securitisation qualifies as a “single issuing body,” as it has no management team or corporate strategy. It is simply a pass-through structure that functions as a steward of the loans and passes through the payments and cash flows.

Given investor control - the risk that the 10% issuer limit seeks to address - is not relevant for securitisations, we see no compelling rationale for retaining the 10% issuer limit for securitisations. If the European Commission wants to achieve its desired outcome of growth in demand for securitisations, removal of the 10% issuer limit is crucial to driving this demand in the asset management sector. While this change could be effected through an amendment to the UCITS Directive, a more efficient and legally viable route may be via clarification under the Securitisation Regulation, which is currently undergoing much needed-reform.

How large could the market grow?

If the rule unintentionally capturing securitisations were relaxed or eliminated, the market could experience significant untapped demand. We estimate that there is €100–€150 billion of potential demand that could be realised immediately, plus an additional €20–€30 billion annually from UCITS investors aloneFootnote5. This would open a new funding and capital channel, complementing banks and insurance demand, and leading to a healthier, more robust, and diversified European securitization market akin to its U.S. counterpart.

What are the risks? Concerns about liquidity are misplaced

Policymakers may be concerned about liquidity if a UCITS rule change allows funds to buy more securitisation assets. However, we believe these concerns are unfounded. Firstly, UCITS funds have strict concentration limits at the fund level, preventing any one position (securitisation or otherwise) from becoming too large. These general limits range from 5%–10% of the market value of the fund.Footnote6 Additionally, UCITS have numerous other restrictions regarding risk management and liquidity that fund managers must consider when evaluating the size and nature of any single position. Arguably, fund managers have a legal obligation and fiduciary duty to manage risks within these guardrails.

Secondly, securitisation liquidity has grown only more robust over time – we would argue it is now comparable to corporate credit liquidity. Indeed, even during stressed situations, like the U.K. LDI (Liability-Driven Management) sell-off at the end of 2022, we saw securitisations perform just as well, if not better, than corporate credit. During that crisis, large amounts of securitisations traded in the market (about 8–12 times the weekly trading volume in normal markets, or approximately $12 billion in around three weeks)Footnote7, with all supply absorbed by trading desks or end-investors, demonstrating market depth even during deep distress.

Lastly, in the U.S., the counterfactual is clear: ‘40 Act mutual funds are not subject to specific limits on securitisations beyond standard concentration limits at the fund level and other fund level limits imposed by individual fund managers. Yet no mutual fund with securitisation exposure had difficulty meeting redemptions in previous periods of stress, most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, the ‘40 Act is a powerful example of how investors can potentially benefit from diversification in a regulated context while supporting the U.S. securitisation market with capital.

Conclusion

We believe it would be a missed opportunity if, after more than a decade of effort building a robust European securitization framework, regulators fail to allow highly regulated UCITS funds to invest more in securitisations, and instead allow securitisations to be purchased and held by private credit funds that are largely unregulated. These private funds often lack stringent investment protections and oversight that UCITS are subject to, potentially exposing investors to greater risks. Such a shift could undermine the progress made in creating a secure and transparent market for securitisations, ultimately jeopardizing the stability and integrity of the financial system and missing the chance to be an engine of growth for Europe.

2 Mario Draghi, “The Future of European Competitiveness,” September 2024, p. 56. Return to content

3 See the EU publication, “Towards a European Market for undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities”. Return to content

4 Based on PIMCO analysis of Bloomberg and available data. Return to content

5 Based on PIMCO analysis of Bloomberg and available data. Return to content

6 Article 52 of UCITS Directive 2009/65/EC. Return to content

7 Based on PIMCO analysis of Bloomberg and available data. Return to content