Modernizing the Diversification Toolkit: Allocating to Defensive Alternatives

We’ve seen increased interest in risk mitigation solutions that combine multiple alternative strategies in an effort to enhance portfolio diversification. We’ve partnered with Paul Murray, an allocator with experience in implementing defensive alternatives for the Future Fund and the Victorian Funds Management Corporation in Australia, to share his insights, along with PIMCO’s perspectives from our partnerships with some of the most sophisticated institutions globally.

Institutional portfolios are often dominated by pro-cyclical risks originating from equity and other long risk-asset exposures that are relied on to pursue long-term positive returns. To sustain pro-cyclical exposures over multi-year horizons, institutional portfolios often make high quality fixed income allocations, where duration exposure is relied on to hopefully buoy portfolios during cyclical downturns. This has broadly worked well across recent decades, and may well continue in the future, but 2022 reminded investors to consider the potential portfolio impact of an abrupt shift in stock-bond correlations from being negative to positive.Footnote1 This correlation regime shift, coupled with high levels of macroeconomic uncertainty around inflation and economic growth, is leading many investors to incorporate defensive alternatives. Investors are realizing the appeal of “diversifying their diversifiers” by embracing new strategies to improve the robustness of their policy portfolio.

While several institutions already have well-established defensive alternatives programs in place, organizational constraints and the complexity of this allocation decision have kept many others at bay. This article is intended to be a guide for asset owners embarking on this journey of re-thinking their allocation. We seek to answer key questions, such as how to determine the opportunity set of strategies for a defensive alternatives program, how to set program goals, and what role certain absolute return strategies and private credit can play. We also provide representative portfolio solutions based on our experience with global asset owners, and share insights on success factors, common pitfalls, and potential risks.

We believe the ultimate key to success when designing a defensive alternatives program is to take a total portfolio approach. It is critical to ensure sizing of various strategies is commensurate with overall objectives of the program and the impact it is intended to have on the overall policy portfolio. This approach contrasts to allocating to defensive strategies strictly within individual asset classes and decision-making units, which may increase overall complexity, reduce scale, and ultimately potentially miss out on the desired results for the overall portfolio.

Investors now have access to a broad toolkit for portfolio diversification

The institutional approach to portfolio diversification has undergone a steady evolution. Whereas cash and core bonds were the typical defensive elements of classic 60/40 portfolios until the 1980s, other assets such as long-duration sovereigns, defensive hedge funds, gold, and commodities emerged over the ensuing decades.

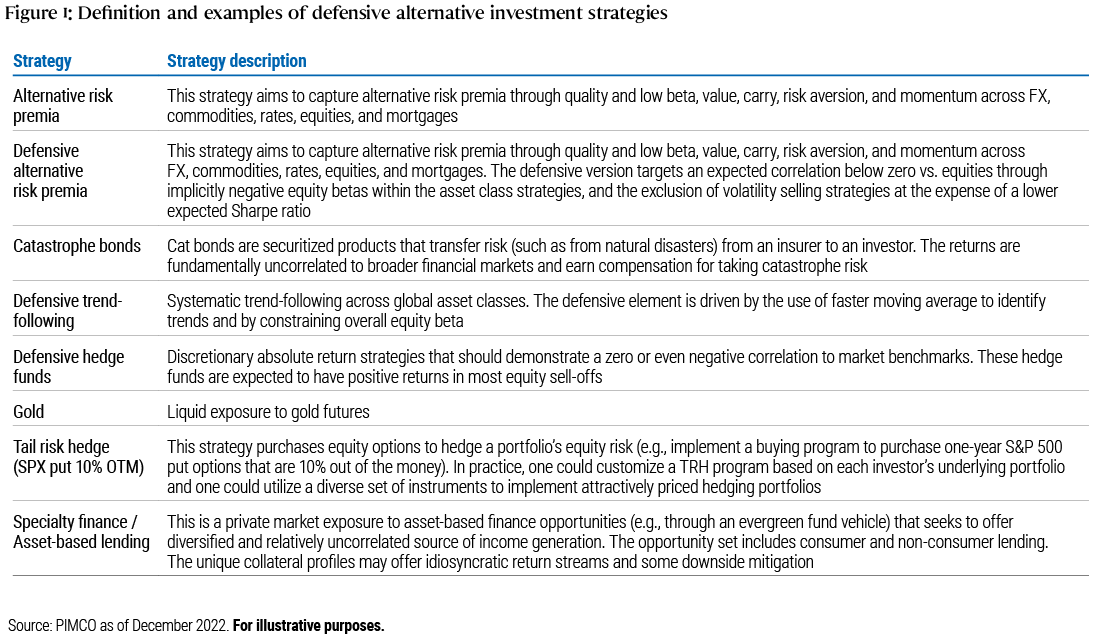

Since the global financial crisis, asset owners have further broadened their toolkit of defensive alternatives through allocations to strategies like managed futures, alternative risk premia, insurance-linked securities, private credit, and tail risk hedges (defined in Figure 1). Some are adopting a capital-efficient approach and employing customized strategies developed jointly with leading investment managers to achieve program goals.

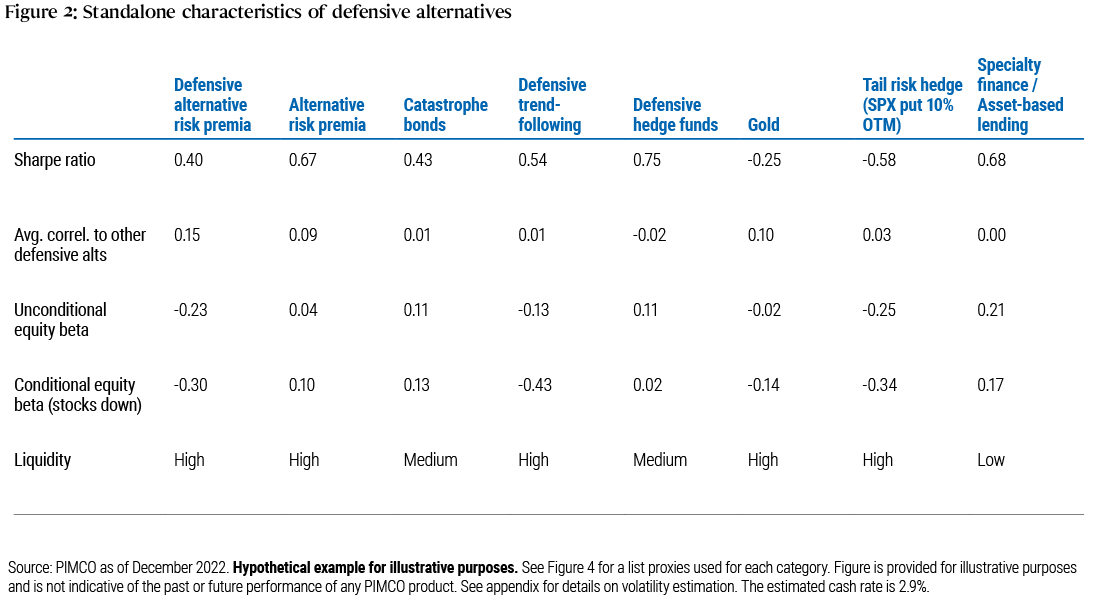

Figure 2 highlights the key characteristics of these strategies, including the estimated forward risk-adjusted returns, based on PIMCO’s capital market assumptions.

Taking a total portfolio approach is optimal when designing a defensive alternatives program

When allocating to defensive alternatives, asset owners may be concerned that individual strategies are more effective in some environments than others. This is why we believe that it is best to take a basket approach. In the 2019 paper “A Theoretical Framework for Equity-Defensive Strategies”, we explained why combining a variety of different strategies that are negatively correlated with equities not only provides a higher degree of confidence with respect to mitigating equity risk, but may also deliver higher returns. In short, we found optimal defensive portfolios exhibited better return-defensiveness properties relative to the underlying strategies on a standalone basis.

Most investors have an allocation to traditional diversifying assets, but either lack a dedicated allocation to defensive alternatives, or have built their allocation without fully considering the overall portfolio. Often, these strategies are sprinkled throughout the portfolio and sized based on the objectives and constraints of the team managing each asset class, instead of focusing on the desired impact on the total portfolio.

So how can investors build robust portfolios of defensive alternatives to cater to disparate investment objectives? Should they optimize the portfolio to maximize risk-adjusted return or to achieve maximum convexityFootnote2 ? In our view, there is no one-size-fits-all solution since the goals, risk-tolerance, starting conditions, fee budget, and governance realities of asset owners will markedly differ. As such, establishing a clear set of goals is perhaps the most important step, taking into account the following parameters:

- Target return

- Evaluation horizon

- Volatility

- Conditional or downside beta to equities

- Gap risk sensitivity (portfolio response to sudden, large market moves)

- Liquidity

- Portfolio yield target

- Fee budget

- Leverage constraints.

Analyzing the trade-off between higher risk-adjusted returns and higher convexity

Based on our experience with global asset owners, there are two distinct investor cohorts when it comes to defining the objectives and the definition of success for a defensive alternatives program:

- Investor A (seeking attractive risk-adjusted returns with low equity beta):

- Primarily focused on maximizing returns with low equity beta (typically <0.3)

- Want the defensive alternative portfolio to generate some income

- Not as concerned about portfolio performance during tail events or liquidity shocks.

- Investor B (seeking negatively correlated returns with high liquidity):

- Focused primarily on minimizing equity beta: typically want it to be zero or negative

- Concerned about performance during tail events

- Plan to use this portfolio as a liquidity source.

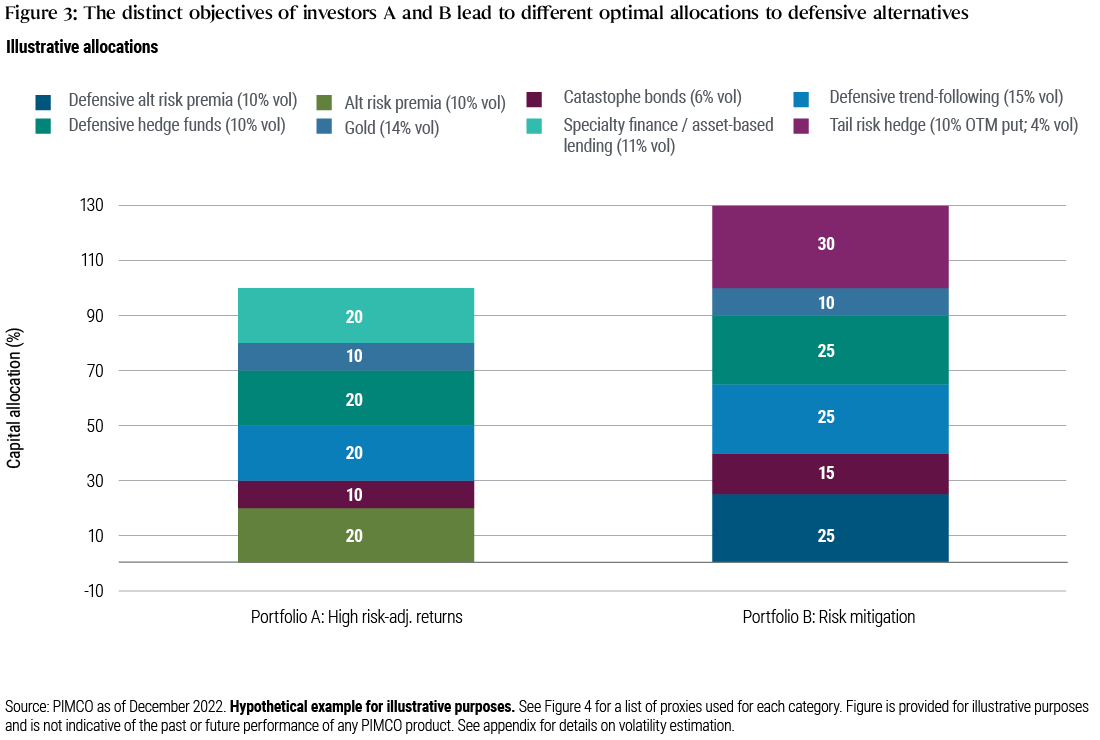

As expected, the “optimal” portfolioFootnote3 looks quite different for these investors. Investor A should, in our view, consider allocating more to private credit (such as specialty finance / asset-based lending) and alternative risk premia (ARP). These strategies have the potential to deliver income and tend to have attractive Sharpe ratios, respectively, while both may exhibit a modestly positive equity beta at times. In contrast, we believe investor B should consider focusing more on defensive ARP and trend-following. These strategies do not necessarily provide income and they generally sacrifice expected return to some extent for the benefit of lower equity beta. In addition, our analysis suggests that investor B should consider allocating to tail risk hedging, which tends to have a negative expected return for the benefit of gap event protection (see Figure 3).

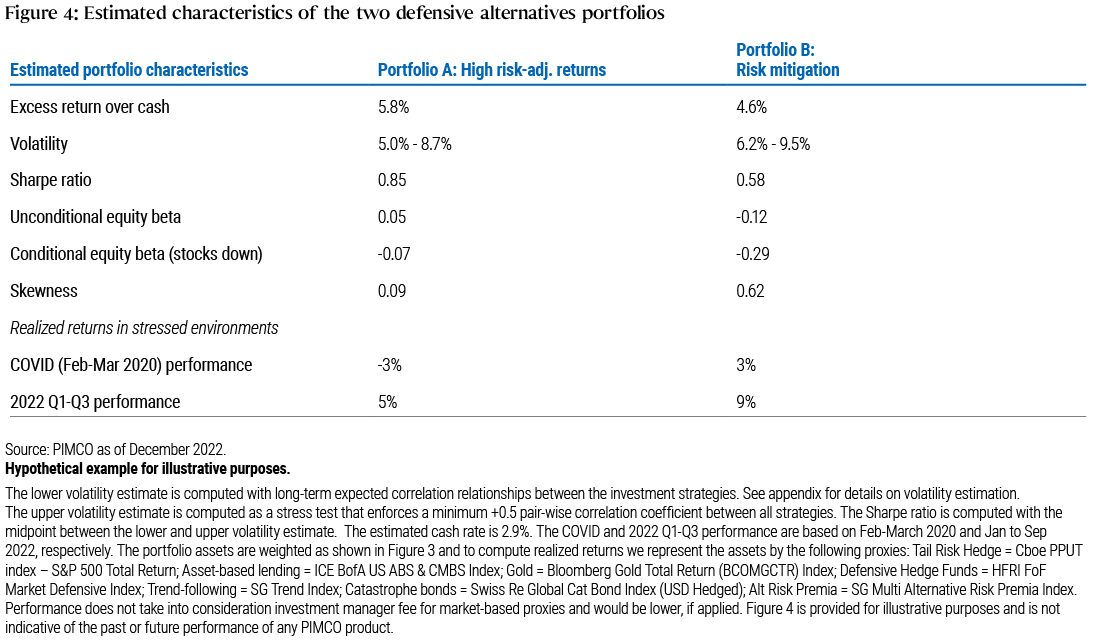

The expected absolute and risk-adjusted returns would be considerably higher for investor A (see Figure 4), which at first glance suggests portfolio A is superior to portfolio B. The unconditional equity beta for investor A is modestly positive, while it is negative for investor B. Both portfolios demonstrate an important attribute of defensive assets – their equity beta is expected to decline in times of market stress. This effect is stronger in portfolio B, which also has a greater positive skewness - a desirable property for financial assets.

As Figure 2 shows, the correlations between the standalone strategies should be low, and in some cases negative. This may result in material diversification benefits when combining defensive alternatives relative to the risk-return tradeoff for each individual strategy.

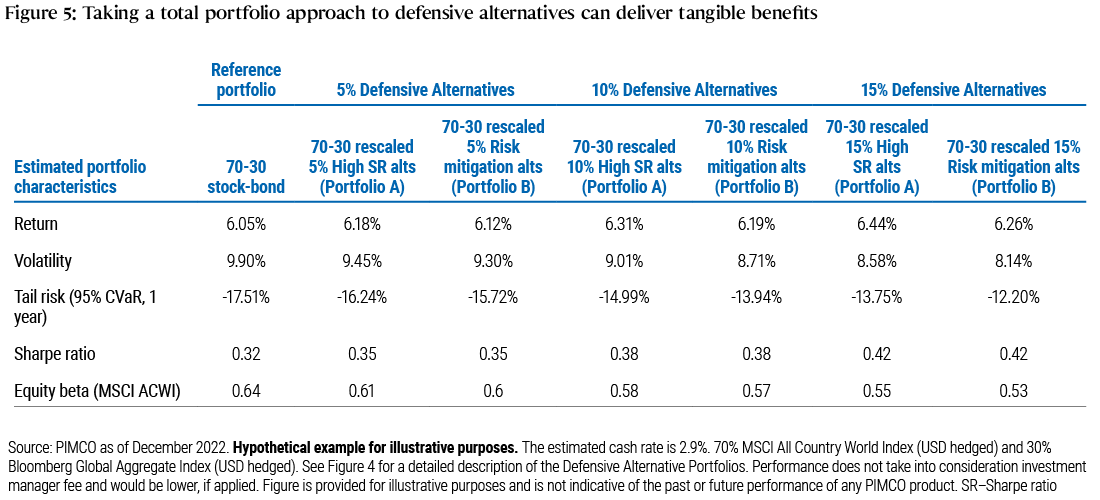

We then assessed the impact of the defensive alternatives bucket on the total portfolio, which we proxy as a standard 70/30 stock-bond allocationFootnote4 . Figure 5 shows varying degrees of pro rata allocation to the two defensive alternatives portfolios. Based on the 70/30 starting point, any pro rata allocation between 5% and 15% to defensive assets increases the total portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns and decreases the tail risk.

With a 10% allocation to defensive alternatives, we find that, even though the standalone Sharpe ratio of portfolio A is meaningfully higher than that of portfolio B, both defensive portfolios increase the Sharpe ratio of the total portfolio by 19%. This is because – relative to portfolio B – portfolio A is more correlated with the 70/30 portfolio and hence offers less marginal diversification benefits. Even adding a modest 5% allocation to defensive alternatives results in a 9% increase in the Sharpe ratio.

The total portfolio perspective particularly highlights the benefits of the risk mitigation portfolio with higher convexity (B) since tail risk is cut by 20% while equity beta is down 11%. Given that both defensive portfolios achieve the same marginal improvement in the Sharpe ratio, but portfolio B offers better tail risk characteristics, it may be considered the superior option for most investors. This is contrary to the initial impression that favored portfolio A based on the standalone risk-return trade-off and is a classic example where asset class-specific optimizations may fail to capture the investor’s overall net benefit.

Given the wide variety of investment objectives, deciding which portfolio may be most appropriate will be up to each investor. Most will likely fall somewhere in between portfolio A and portfolio B.

Key elements to establishing a well-designed and well-executed defensive alternatives program

While we believe there are tangible benefits to be realized from taking a total portfolio approach, implementing a 10% change to a sophisticated institutional portfolio is no small task. Effective implementation of a defensive alternatives program requires careful consideration of all stakeholder requirements, alignment with the asset owner’s investment objectives, and creation of a framework to manage the impact on investment process and team structure.

The fact that optimal portfolio construction at the asset class level may differ from the allocation that is most beneficial for the overall portfolio can create organizational frictions and incentive alignment issues since the responsibility for total portfolio decisions needs to be incorporated into the decision-making process. An associated challenge is whether the asset owner should establish a dedicated team and asset class allocation bucket, or adapt existing exposures that may be dispersed across various teams such as fixed income, credit, private markets, and hedge funds.

Allocators also need to be prepared to endure periods of time where their defensive alternatives allocation may underperform. Setting clear performance expectations across various market scenarios can improve understanding and align the program with diverse stakeholder perspectives.

Based on our experience of implementing a program and overcoming such obstacles, we have identified two key pitfalls: risk “underutilization” and risk “over-diversification”.

Below we share some options for asset owners to ease the burden of making changes to portfolio design when including defensive alternatives.

Underutilizing defensive alternatives

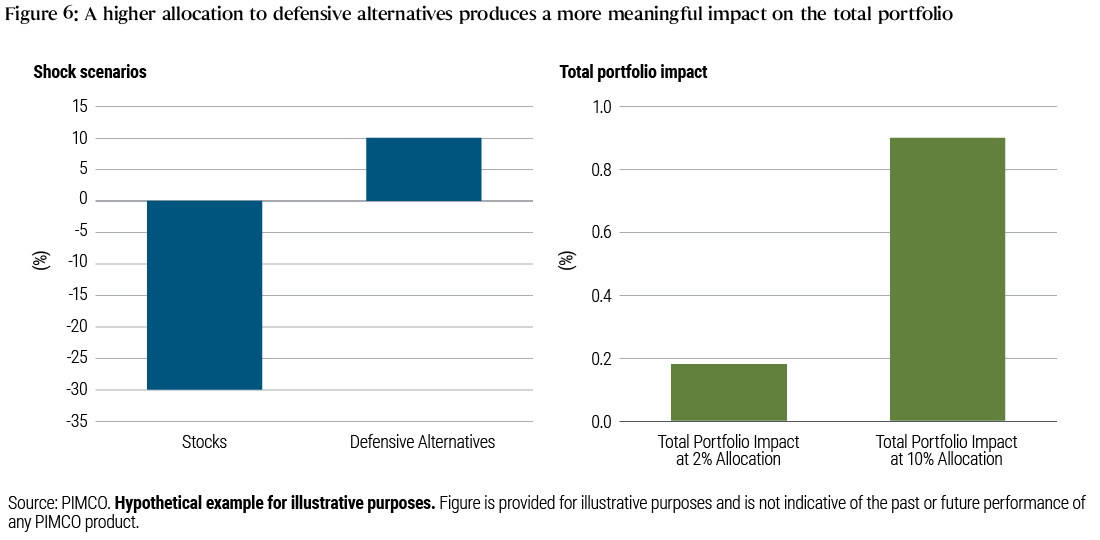

Investors typically seek to make changes incrementally to test an idea, establish capacity, and/or minimize the risk of a mistake. A common pitfall is to allocate too little risk to new initiatives, which may result in successful ideas not realizing their full potential or making an insufficient impact on the total portfolio. Figure 6 illustrates the impact of a sharp 30% sell-off in equities. With a conditional equity beta of -0.3, the risk mitigation portfolio (B) is estimated to return +9%. If the defensive alternatives program is sized at 2%, this only equates to a 18 basis point (bp) performance contribution to the total portfolio. At a 10% sizing, the overall portfolio-level performance contribution of close to +1.0% is much more meaningful. It also leads to higher reduction in the total portfolio’s volatility, and returns generated could be used as a source of liquidity to buy risk assets potentially cheaply.

We believe underutilization is a problem of perceived rather than actual risk. Given the expected outcomes for defensive alternatives are typically new to investment teams and not well understood in terms of their defensive properties, they are often labeled “too good to be true”. This can lead to an underweight allocation that limits the potential benefits.

We believe that a phased approach can help mitigate underutilization of risk. We suggest establishing a roadmap for the defensive alternatives program, which makes the case for the new allocation and how the allocation could increase over time. It would include the definition and scope of the opportunity, plus a detailed plan of staged allocation targets over a three-year horizon. Specifically, it can be helpful to establish and publish long-term allocation objectives so that stakeholders are able to evaluate the impact relative to the stage of implementation. It is important to have clear criteria for assessing how the program is tracking to the plan in terms of realized total portfolio impact. This can help to demystify the allocation for stakeholders and simultaneously measure the opportunity costs of not abiding by the plan.

A phased approach with clear long-term goals allows all stakeholders to evaluate the new allocations, and to gain experience with how they interact with the entire portfolio. Importantly, because the justification for adding defensive alternatives relies on a total portfolio perspective, a phased approach can help reinforce this view while mitigating the risk of outlier performance in early years.

Further, a critical feature of many defensive alternative strategies is capital efficiency, which allows stakeholders to view the new allocation as a positive-sum contribution to the total portfolio. Rather than taking capital away from an existing allocation to support defensive alternatives, allocators can work with investment managers to structure capital-efficient solutions that can use existing or otherwise desired allocations to support defensive alternatives. For example, a cash bond portfolio could support derivative overlay strategies, such as trend-following or ARP. This requires investors to think in terms of risk budgets calibrated to the desired total portfolio impact, rather than capital allocated. This approach may be particularly helpful when the ability to source capital from existing exposures is limited.

In contrast to the more common problem of under-allocating risk to defensive alternatives, investors should also be mindful of potentially oversizing the defensive alternatives portfolio. Mean-variance optimization algorithms will generally recommend large allocations to defensive alternatives if the expected return is equity-like and the correlation to growth assets is low. We think that it is important to overlay these quantitative results with qualitative analysis, acknowledging that highly diversifying strategies have inherently unusual distributions of outcomes that cannot be simply evaluated in the same terms as traditional assets. For example, assuming a normal distribution of returns for trend-following ignores a key feature (positive skewness) that justifies the allocation to that strategy.

In summary, we suggest that allocators think big when designing defensive alternative allocations, and plan for realistic friction when introducing strategies with inherently unfamiliar characteristics to an established portfolio. A phased approach with clear long-term goals can help stakeholders buy in, and considering capital-efficient solutions may create positive-sum outcomes for mature portfolios.

Over-diversifying defensive alternatives

Another common pitfall is to over-diversify exposures within the defensive alternatives portfolio. The motivation may be similar to under-allocating risk and reflect a lack of conviction in the role of alternatives in the portfolio. These strategies are inherently more complex than plain vanilla stock or bond investments, requiring the asset owner to fully understand the opportunity to capitalize on the complexity.

While risk dispersion is appropriate to some extent, the selection of a large set of investment managers to manage a small fraction of the total portfolio may result in a poorly constructed portfolio. It would not only increase the required monitoring, but could result in offsetting alpha trades to the extent that managers have opposing investment views, which could create inefficiencies and lead to a high fee burden.

In our view, it is important to build conviction in specific strategies and in investment managers through a qualitative and quantitative due diligence process. Given the process of understanding, evaluating, and building confidence takes time, the roadmap discussed previously should also be beneficial to help prevent over-diversification. The optimal outcome would be a complete understanding of risk within the defensive alternatives portfolio, and in turn, risk at the total portfolio level.

Having a smaller set of investment managers acting as strategic partners may be beneficial when designing this type of program. A partner can provide the necessary transparency into detailed risk exposures of quantitative and hedge fund strategies, which is a required input for portfolio construction and risk management at the asset owner level. In addition, strategic partners with broad absolute return and risk analytics platforms have the ability to tailor investment solutions to asset owner requirements. A manager’s past experience of customizing similar portfolios across discretionary and systematic strategies should allow them to provide practical insight into optimal alternatives portfolio construction.

Adopting a partnership approach should not only lead to improved portfolio outcome potential, but also better access for asset owners to potentially capacity-constrained strategies. It should also align objectives between the asset owner and manager, which can accelerate a shift away from asset classes operating within a silo and toward a total portfolio approach that uses risk more effectively.

Conclusion

Asset owners face several challenges in building an efficient defensive alternatives portfolio. It is important for investors to set clear and comprehensive objectives and acknowledge trade-offs among implementation options. Two common pitfalls are an under-allocation of risk to this asset class and over-diversification of exposures within the asset class. We believe these pitfalls can be managed by taking a phased and committed approach that raises exposure in a capital-efficient manner by building conviction in and working closely with a select set of strategic partners that have experience in designing and implementing customized defensive alternatives strategies.

In our view, the benefits of taking a total portfolio approach clearly outweigh the costs over the long term. We find that incorporating a mix of defensive non-traditional assets leads to meaningful diversification benefits and a portfolio of such assets may offer attractive returns with Sharpe ratios close to 1.0.

Most importantly, we expect these portfolios to have a materially positive impact on the overall portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns and left tail risk. In particular, defensive alternatives portfolios that are designed to demonstrate convex characteristics likely offer much needed diversification benefits for typical pro-cyclical multi-asset portfolios.

Appendix

CORRELATION

The correlation of various indices or securities against one another or against inflation is based upon data over a certain time period. These correlations may vary substantially in the future or over different time periods that can result in greater volatility.

CVAR

Conditional Value-At-Risk (CVAR). This is computed as the average return in the worst 5% of months ranked by return. It is a measure of tail risk over a one-year horizon.

VOLATILITY (ESTIMATED)

We employ a block bootstrap methodology to calculate volatilities. We start by computing historical factor returns that underlie each asset class or investment strategy model from January 1997 through the present date. We then draw a set of three-month returns within the data set to come up with an annual return number. This process is repeated 25,000 times to have a return series with the same number of annualized returns. The standard deviation of these annual returns is used to model the volatility for each factor. We then use the same return series for each factor to compute covariance between factors. Finally, volatility of each asset class or investment strategy proxy is calculated as the sum of variances and covariance of factors that underlie that particular proxy. When we refer to conditional subsamples, we use historical samples under a stressed period, determined by filtering on monthly periods where US equity returns are negative.

1 The correlation between weekly total returns of S&P500 and Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index was +0.38 from 12/31/2021 to 12/30/2022.Return to content

2 Convexity represents the potential for increasing diversification during larger equity market drawdowns. In this context, high convexity implies a large negative equity beta when stocks are down.Return to content

3 We run an optimization that maximizes estimated return for a given level of volatility (and conditional equity beta). We use custom risk models for the alternatives strategies as well as reasonable optimization constraints for leverage, diversification, and equity beta.Return to content

4 70% MSCI All Country World Index (USD hedged) and 30% Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index (USD hedged).Return to content

Featured Participants

Disclosures

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results.

The analysis contained in this paper is based on hypothetical modeling. HYPOTHETICAL PERFORMANCE RESULTS HAVE MANY INHERENT LIMITATIONS, SOME OF WHICH ARE DESCRIBED BELOW. NO REPRESENTATION IS BEING MADE THAT ANY ACCOUNT WILL OR IS LIKELY TO ACHIEVE PROFITS OR LOSSES SIMILAR TO THOSE SHOWN. IN FACT, THERE ARE FREQUENTLY SHARP DIFFERENCES BETWEEN HYPOTHETICAL PERFORMANCE RESULTS AND THE ACTUAL RESULTS SUBSEQUENTLY ACHIEVED BY ANY PARTICULAR TRADING PROGRAM.

ONE OF THE LIMITATIONS OF HYPOTHETICAL PERFORMANCE RESULTS IS THAT THEY ARE GENERALLY PREPARED WITH THE BENEFIT OF HINDSIGHT. IN ADDITION, HYPOTHETICAL TRADING DOES NOT INVOLVE FINANCIAL RISK, AND NO HYPOTHETICAL TRADING RECORD CAN COMPLETELY ACCOUNT FOR THE IMPACT OF FINANCIAL RISK IN ACTUAL TRADING. FOR EXAMPLE, THE ABILITY TO WITHSTAND LOSSES OR TO ADHERE TO A PARTICULAR TRADING PROGRAM IN SPITE OF TRADING LOSSES ARE MATERIAL POINTS WHICH CAN ALSO ADVERSELY AFFECT ACTUAL TRADING RESULTS. THERE ARE NUMEROUS OTHER FACTORS RELATED TO THE MARKETS IN GENERAL OR TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF ANY SPECIFIC TRADING PROGRAM WHICH CANNOT BE FULLY ACCOUNTED FOR IN THE PREPARATION OF HYPOTHETICAL PERFORMANCE RESULTS AND ALL OF WHICH CAN ADVERSELY AFFECT ACTUAL TRADING RESULTS.

Because of limitations of these modeling techniques, we make no representation that use of these models will actually reflect future results, or that any investment actually will achieve results similar to those shown. Hypothetical or simulated performance modeling techniques have inherent limitations. These techniques do not predict future actual performance and are limited by assumptions that future market events will behave similarly to historical time periods or theoretical models. Future events very often occur to causal relationships not anticipated by such models, and it should be expected that sharp differences will often occur between the results of these models and actual investment results.

Return assumptions are for illustrative purposes only and are not a prediction or a projection of return. Return assumption is an estimate of what investments may earn on average over a 5 year period. Actual returns may be higher or lower than those shown and may vary substantially over shorter time periods. Return assumptions are subject to change without notice.

Forecasts, estimates and certain information contained herein are based upon proprietary research and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. There is no guarantee that results will be achieved.

Figures are provided for illustrative purposes and are not indicative of the past or future performance of any PIMCO product.

All investments contain risk and may lose value. Catastrophe (Cat) Bonds are insurance securitizations, structured similarly to traditional bonds, where a specified set of risks is purchased by investors; if a triggering catastrophe occurs prior to maturity investors may lose most or all of their accrued interest and principal. Commodities contain heightened risk, including market, political, regulatory and natural conditions, and may not be appropriate for all investors. Hedge fund and other alternatives strategies involve a high degree of risk and prospective investors are advised that these strategies are suitable only for persons of adequate financial means who have no need for liquidity with respect to their investment and who can bear the economic risk, including the possible complete loss, of their investment. Performance could be volatile; an investment in a fund may lose money. Tail risk hedging may involve entering into financial derivatives that are expected to increase in value during the occurrence of tail events. Investing in a tail event instrument could lose all or a portion of its value even in a period of severe market stress. A tail event is unpredictable; therefore, investments in instruments tied to the occurrence of a tail event are speculative. Derivatives may involve certain costs and risks such as liquidity, interest rate, market, credit, management and the risk that a position could not be closed when most advantageous. Investing in derivatives could lose more than the amount invested. Equities may decline in value due to both real and perceived general market, economic and industry conditions. Diversification does not ensure against loss.

Asset allocation is the process of distributing investments among various classes of investments (e.g., stocks and bonds). It does not guarantee future results, ensure a profit or protect against loss. There is no guarantee that these investment strategies will work under all market conditions or are appropriate for all investors and each investor should evaluate their ability to invest long-term, especially during periods of downturn in the market. The allocation models are not based on any particularized financial situation, or need, and are not intended to be, and should not be construed as, a forecast, research, investment advice or a recommendation for any specific PIMCO or other strategy, product or service. Individuals should consult with their own financial advisors to determine the most appropriate allocations for their financial situation, including their investment objectives, time frame, risk tolerance, savings and other investments.

Bloomberg Global Aggregate (USD Hedged) Index provides a broad-based measure of the global investment-grade fixed income markets. The three major components of this index are the U.S. Aggregate, the Pan-European Aggregate, and the Asian-Pacific Aggregate Indices. The index also includes Eurodollar and Euro-Yen corporate bonds, Canadian Government securities, and USD investment grade 144A securities. Bloomberg Gold Total Return Index reflects the return of fully collateralized positions in the underlying gold futures. The Cboe S&P 500 5% Put Protection IndexSM (PPUT) tracks the value of a hypothetical portfolio of securities (PPUT portfolio) designed to protect an investor from negative S&P 500 returns. The PPUT portfolio is composed of S&P 500® stocks and of a long position in a one-month 5% out-of-the-money put option on the S&P 500 (SPX put). strong>HFRI Market Defensive Index, is an unmanaged index that includes FOFs classified as 'Market Defensive' that exhibit one or more of the following characteristics: invests in funds that generally engage in short-biased strategies such as short selling and managed futures; shows a negative correlation to the general market benchmarks. A fund in the FOF Market Defensive Index exhibits higher returns during down markets than during up markets. ICE BofA U.S. ABS & CMBS Index tracks the performance of U.S. dollar denominated investment grade fixed and floating rate asset backed securities and fixed rate commercial mortgage backed securities publicly issued in the U.S. domestic market. The MSCI All Country World Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization weighted index that is designed to measure the equity market performance of developed and emerging markets. The Index consists of 47 country indices comprising 23 developed and 24 emerging market country indices. The SG Trend Index calculates the net daily rate of return for a group of 10 trend following CTAs selected from the largest managers open to new investment. The SG Trend Index is equal-weighted and reconstituted annually and has become recognized as the key managed futures trend following performance benchmark. The SG Multi Alternative Risk Premia Index represents risk premia managers who employ investment programs diversified across multiple asset classes while utilizing multiple risk premia factors. S&P 500 Index is an unmanaged market index generally considered representative of the stock market as a whole. The Index focuses on the large-cap segment of the U.S. equities market. Swiss Re Global Cat Bond Index tracks the aggregate performance of all catastrophe bonds issued offered Rule 144A. The index captures bonds denominated in any currency, all rated and unrated cat bonds, outstanding perils, and triggers. It is not possible to invest directly into an unmanaged index.

PIMCO as a general matter provides services to qualified institutions, financial intermediaries and institutional investors. Individual investors should contact their own financial professional to determine the most appropriate investment options for their financial situation. This material contains the opinions of the manager and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This material has been distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission. PIMCO is a trademark of Allianz Asset Management of America LLC in the United States and throughout the world. ©2023, PIMCO.