Stay tuned after the conclusion of the podcast for additional important information.

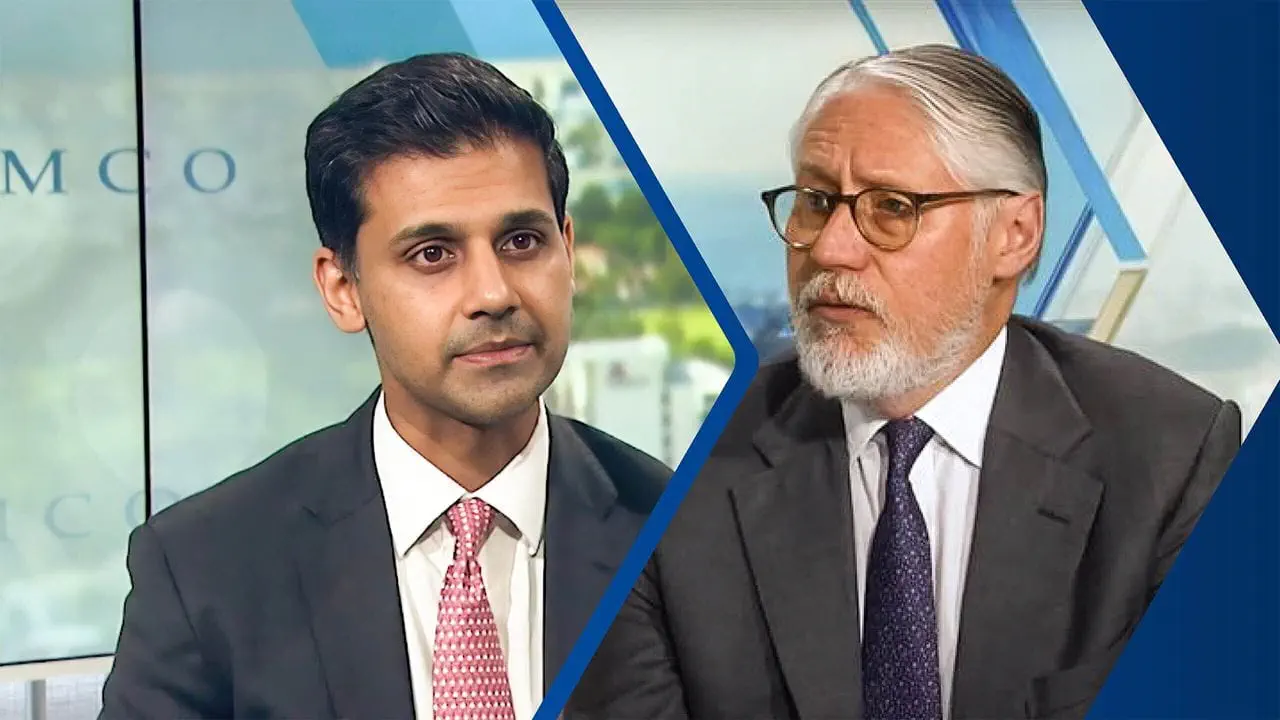

GREG HALL: Hey, everybody! Welcome to another episode of Accrued Interest PIMCO's podcast, dedicated to serving financial advisors and their clients. My name's Greg Hall. I head the Wealth Management Business for PIMCO here in the United States. And as always, I'll be your host. It's Fed Day. It's September 17th, 2025.

This is the meeting that we have all been waiting for the lead up to, which has been perhaps more dramatic than you know, these meetings tend to be. And so we are fortunate enough in today's conversation to have had Rich Clarida. Dr. Clarida, you may remember from our February episode as a global economic advisor for PIMCO. He served as Vice Chair of the Fed with Jay Powell until 2022. And prior to that stints at the Treasury Department a long career of both government service as well as education.

He's a Professor as well. And we get to that over the course of the conversation. The meat of the conversation today is, as you'd expect, it's a rundown in reaction of today's Fed meeting, the quarter point cut, the implications for the months ahead of us, as well as you know, Rich's analysis of, you know, how that decision probably came to be and what some of the individual votes of the Fed Governors might mean you know, for predicting that body's development.

You know, both from an economic standpoint, a political standpoint, given the fairly unique circumstances we find ourselves in. Today, we talk a little bit about for lack of a better word, the palace intrigue around some of the Governors themselves and what may or may not be politically motivated attempts to steer the Fed's direction and the broad, you know, state of Fed and independence at this point.

And then finally, and I really, I'm not just saying this because we put a lot of time and effort into the podcast, but I'd encourage you to stick around to the end. We got into a philosophical conversation that turned into a historical conversation where Rich really explains some of the tensions that the Fed needs to balance in pursuit of its mandate.

And also some of the events under previous administrations and previous points in history that actually led to you know, the decisions that set up you know, the modern Fed as it exists today. And it's for any of you who are fans of economics and economic history, it's an opportunity to sit in class with Professor Clarida and learn a lot about some of the principles and the antecedents that lead to today's Fed.

So I hope you enjoy it. I would be remiss if I didn't ask you to please if you're enjoying the podcast hit like, subscribe let us know that you're out there. If you'd like to learn more about any of the comments or views that were expressed in today's podcast, please visit us, our website's, pimco.com here in the US.

And if you identify yourself as a financial advisor, you'll be taken to Advisor Forum that is our destination for you as financial advisors to get the information that you need from us as quickly and practically as possible, and send you on your way armed to do a great job on behalf of your clients. Thanks so much! And here's my conversation with Rich.

GREG HALL: Hey, Rich, great to see you! Thanks for joining us!

RICH CLARIDA: Looking forward to it!

GREG HALL: Pretty busy day for you. I'm sure, on as Fed days always are. Appreciate you carving time out of your schedule. I know you are busy advising our portfolio management teams, I'm sure, speaking directly to clients as well, and in between all that, no doubt, digesting the news yourself and coming to your own conclusions.

RICH CLARIDA: That's right! And also did the typical IC discussion right after the press conference as well.

GREG HALL: Alright, good. Well, so we're catching you hot off the presses with, you know, UpToDate takes on, what we heard from today. So why don't we just get, you know, right into it. I mean, I, with all the drama leading up to the meeting. It seemed to me, you know, as a more casual observer than you certainly that we got a pretty much as expected result. What was your take?

RICH CLARIDA: Well, yes, the rate cut of 25 was telegraphed, so that was as expected. But there were a fair number of surprises. How can there be surprises if we knew the decision? Well, there were a surprise in terms of the vote. So, for example, there was only one descent, which everyone expected that Steve Miran, once he got sworn in, which happened hours ago, that he would dissent and he did dissent in favor of 50. I was surprised that that was the only dissent. I thought that we could get a dissent from Waller and potentially Bowman for also a 50 basis point cut. And we didn't on the...

GREG HALL: They were the ones who had dissented in July. Am I remembering that? Okay.

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah. And then importantly, I also thought we could get at least one dissent in favor of no cut in the end that did not happen. So I think that was a surprise. The other thing that was a bit of a surprise, although it was a close call is that the infamous dot plot showed that you had a very slim majority of 10 of the 19 folks around the table indicating two more cuts this year. So for a total of 75 this year.

And we had really been on the bubble about whether or not the dots would show a total of two or three cuts for the year. So that was also interesting as well.

GREG HALL: Yeah, I thought it was interesting as well that particularly Bowman and Waller seemed to have, you know, kind of come back into the fold, if you will. And I wanna, I do wanna talk about the human dynamics of this meeting, but maybe before we move on to that very interesting aspect of this, if we just stick with the fundamentals.

Did you pick up anything either from the statement or from Powell's press conference afterwards that gave us any additional insight into how he's looking at the data, what we should expect going forward here?

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah, absolutely! In fact, in that sense, I think there was a lot of useful information. So both in the FOMC statement, and no fewer than six times in the press conference did Powell talk about uncertainty, elevated uncertainty, and also risk management.

So downside risk to the employment outlook. So I think that if I were gonna tie this up in the bow, the justification for this 25, was really a risk management justification that they still are projecting a relatively low unemployment rate for the rest of the year, and they're not really projecting a recession. But nonetheless, they felt that on risk management considerations that they wanted to not only deliver the 25, but also signal an additional 50 basis points of cut.

I would also argue, Greg, there was maybe some risk management behind the scenes, and we'll get to that in terms of keeping the committee together and really limiting the dissents to Miran. My sense is it probably took some work on Jay's part to get that done, but he pulled that off as well.

GREG HALL: It’s so fascinating and I'm dying to get there. I promised myself we would sort of stick with some of the data and the fundamentals. First, did you, you know, when you think about that risk management cut, you know, the way I was thinking about it in my head is, you know, basically just trying to cut off that left tail of outcomes.

And my sense is that's predominantly because of the weakening employment data that we've seen of late. Is that, was that your sense and is that what we heard?

RICH CLARIDA: One hundred percent. It is a labor market as the, as Fed officials will remind you till they, and you are blue in the face the Fed has a dual mandate which is both price stability and maximum employment. And if they were just doing this solely based on inflation, they wouldn't be cutting. 'cause it's obviously close to 3% now. But, they are focused on the labor market. We had a very disappointing print in, for the August release, what we got in September.

And then obviously the massive revisions that came out a week ago, which showed that about nearly a million jobs that had been counted as created in the last 12 months disappeared. And so you combine those revisions with the very weak number that we got, and I think it was a pretty straightforward call to get at least 25 basis point cuts, again, on risk management considerations.

GREG HALL: Was the only offset to that, the potential for inflation coming through because of tariffs? Or are there other economic indicators that you think they would've been weighing against the job numbers? I know we had a pretty solid consumer

RICH CLARIDA: Retail sales.

GREG HALL: Yeah like I'm wondering what the histogram of data looks like in addition to just the jobs numbers.

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah. Well, they're, you know, when the Fed says they look at everything, it really is true. In fact, especially with regards to the labor market, there are dozens and dozens and scores and scores of graphs and charts and tables and regressions that they'll be looking at in the staff briefing. So it's not just the unemployment rate, you know, up through the June and July meeting, you know, Powell was actually quite precise in saying, look, yes, employment growth has slowed.

But that's also because the supply, the growth and the supply of labor has slowed because of the immigration changes in immigration enforcement. And so he, I think at one point, maybe at Jackson Hole, he talked about a curious balance in the labor market. So I think the combination of that August data and the revisions has pushed Powell and the committee away from the curious balance to an outright risk management cut. And so, but looking at a lot of data, not just the unemployment rate.

GREG HALL: For sure. And it feels like, I mean, I don't know where markets have closed today, but it felt like, at least in the immediate aftermath you know, we saw a little bit of a mixed reaction. Rates sold off, they came back, stock sold off, they came back. It does seem like the market's treating this more or less like a consensus outcome.

RICH CLARIDA: Yes. I think initially rates fell five basis points or so on the 75 for the year and the dots as opposed to the 50. But even going into the press conference, that began to reverse, I think the press conference at best was a mixed bag, maybe a bit more hawkish, and so. I think we pour more or less ended markets into more or less ended close to where they were going into the Fed decision, yeah.

GREG HALL: Is that of, because when people hear risk management rate cut, it's not so much that they don't agree with the thesis of risk management. It's kind of what it's not, right? It is not the automatic beginning of a long cycle of deep rate cuts.

RICH CLARIDA: Well, and to me here, this was the money quote. So I actually wrote it down. I'm gonna read it now.

GREG HALL: Good! Good! Good!

RICH CLARIDA: At one point, and this is the J Powell, I know, well, he said, quote, it's not incredibly obvious what the Fed should do next. And so if you wanted a way to sort of tamper enthusiasm for a bunch of rate cuts down the road, that's what you would, that's what you would say. So…

GREG HALL: That is radical transparency. It's good to lead with vulnerability and admit when you know, you don't know. Although I guess he's been, very, you know, forward about not, he doesn't wanna be predisposed to an outcome.

He wants to let the data, you know, determine the path and maybe on the data point you know, and especially you guys having just maybe, you know, had some conversations in the IC did we, do we think Powell is interpreting the data that we have Ben and what do you think we'll be looking at in the data in the next coming months to sort of see how much conviction we wanna put into that dot plot? If it's a little bit uncertain right now, how do you think we're gonna gain certainty around it?

RICH CLARIDA: I think our focus and the Feds will be on the labor market data. I think the inflation numbers are coming in probably better than folks thought on Liberation Day, but more or less in line with where we've been since the summer. So I think at the margin, the marginal data that could influence decisions are gonna be the labor market data.

You know, that being said, you know, Atlanta Fed tracking and other tracking, the retail sales numbers that we got are pretty darn healthy, you know, GDP growth in the first half of the year averaged about one and a half percent. Some folks have the Q3 number, and of course, we won't get that day until the end of October, have the Q3 number somewhere in the high twos, or in some even close to three annualized.

And then of course, as we discussed at our cyclical forum, and we'll be obviously talking about that more in coming weeks there is strong spending in CapEx especially, you know, data centers and tech spending. There will be refund checks that start to get sent out in 2026. And then a lot of companies as part of the trade negotiations with the White House have promised to make capital spending plant equipment investment in the US.

And so, you know, as you look out longer term into the end of this year and into 2026, then there's a lot of data, not just the labor market, that becomes a focus as well.

GREG HALL: Any additional thoughts on, I think the last time we spoke to you was well before Liberation Day. We haven't really had a chance to catch up with you, at least in this format, since. Any additional thoughts on why inflation isn't more apparent given the fact that even we haven't had the draconian tariffs that were pushed out on Liberation Day, but we've certainly raised the average level pretty significantly. And I know every, it's waiting for [UNCLEAR], you know, it just doesn't seem to show up. Any thoughts there?

RICH CLARIDA: So there are couple of things. It is true that overall inflation has not moved up. And that's what Bessent and others make reference to. But, the reason why the overall inflation rate has not increased is because the increase in goods price inflation that you can attribute to tariffs has been offset by a decline in inflation in the services part of the economy.

So the counterfactual, I think, you know, would be that if we had no tariffs right now, then probably we would've seen inflation actually coming down, not just staying the same. So I think that's basically the story. It is showing up in goods price inflation, not, but not in an extreme way. So, you know, certainly if you and I had done this podcast on Liberation Day when we were talking 20 and 30% tariffs,

GREG HALL: I'm glad we didn't do that to you, Rich. I think that would've been tough one to be accurate with.

RICH CLARIDA: But, so part of it is simply that the ultimate tariffs, in particular, the headline tariff on Canada and Mexico is off the charts, but most of it is exempt because of the prior trade deals. And so that's part of it. The other part, and you know, Tiffany and Allison Boxer and our team have done a good job in this.

The other part is that it has been absorbed either in profit margins or it's actually been absorbed in terms of scaling back in employment. So companies are adjusting to tariffs, but they are, at least in the aggregate, not passing it all through to the final consumer. You know, there are some well-known cases, you know, in particular, some big box retailers have been highlighting that in particular, so…

GREG HALL: Sure, sure. And some folks have been chastised as well for, you know, claiming that they would need to pass those price increases on. So you referenced Tiffany Wilding and Allison on our macroeconomic team, and we'll link to some of their recent research in the show notes here.

It's really interesting, and we can't dwell on it today, but I think it's just a really interesting dynamic to think about how the potential price increases work their way through inventories that were accumulated, because the tariffs were well heralded.

And so accumulated inventories, and then how much can companies take in terms of profit squeeze? And I hadn't thought about it, but of course, you're right to point out that part of company's cost structure is labor. And so job reduction helps, or…

RICH CLARIDA: At least a slowdown in employment growth. Yeah, yeah.

GREG HALL: Sure. Sure. So that'll be a fascinating thing to watch unfold in the coming months. I noticed in Powell's statement the tariff, the T word as they say, did not appear, but he did reference goods inflation, right? Which I would imagine is a fairly calculated decision on this part.

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah, yeah. Yeah. Again, I think, look, I was in the camp that thought the pass through from the tariffs to inflation would be more significant than we've seen. And I think you do, if you're a Fed official, you want to take signal. Mary Daly in San Francisco's done a good job at sort of highlighting the evolution of her thinking as well. I guess I just wanna set this record straight.

It is not true, as some folks have said that there is no evidence of tariffs in the inflation data. It is there, it's showing up in goods inflation. It's actually showing up in the sectors most exposed to tariffs, but it's being offset by the services part of the economy and other adjustments, if we just discussed, yeah.

GREG HALL: Sure. Yeah. And that, again, that's just being having allegiance to the data, which is of course what we do. And what Powell has said that he and the Fed will do. Any, you want to venture or any thoughts on terminal rate at this point? Knowing what we know now, or is it still a little murky to voice an opinion there?

RICH CLARIDA: Well, okay. So I think, you know, not to toot our own horn, but one of our themes now for more than a decade has been this idea of a new neutral. And our view really, I think for the last three or four years is neutral, may have drifted up a bit, but it's been around 3% now, and that happens to be where the long run Fed dot is, that is where market pricing is more or less for the terminal rate.

Now, importantly we won't know the terminal rate till we actually get there. And to some extent, it really comes down to or we gonna have a soft landing or hard landing? So if you have a soft landing, then a terminal rate in the 3% range, say three and a quarter, 275, that's more or less what's priced in.

That's where the Fed is, that's where the primary dealers are. However, you know, we haven't repealed the business cycle. If we have a recession between now and then, then the Powell Fed, or the Kevin Hassett Fed, or the Chris Waller Fed, or the Kevin Walsh Fed or whoever's on that list, will cut rates below neutral. That's what the textbook says they should do. But, terminal rate in the context of a soft landing is we think around 3%.

GREG HALL: Yeah. We haven't repealed the business cycle, although fewer and fewer of us are old enough to remember the last time that we had one, right?

RICH CLARIDA: Well, we were all around for the two months of 20 March and April of 2020 when we had a technical recession. I'd like to think the good monetary policy had something to do with making that a brief recession, but yeah.

GREG HALL: Well, yeah, sure. I get compliments all around, present company included. So let, yeah, let's do, talk about the, I hate to say it, but you know, the palace intrigue. I was reading, I want to credit the Wall Street Journal for this, but they referred to it as the strangest Fed meeting ever on the way in.

And you, having been in those meetings, and, you know, lots if not all of the players, I don't wanna get gossipy here. But I'm really curious to hear your interpretation of everything that's gone on over the last few months, and specifically very curious how you think that may have influenced this meeting and this decision.

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah. Well, a lot has gone on. As I think we probably discussed the last time I did this podcast, you know, it's not unheard of in Fed history for Presidents to criticize the Fed. In fact, it was the norm. If you go back, you know, into the 1950s and sixties and seventies, or we actually have evidence that the Nixon administration put a lot of pressure and succeeded.

What has happened in the last 30 years before President Trump is that White Houses were discreet about criticizing the Fed publicly, although sometimes in back channels that happened. And so really both in Trump 1.0 and Trump 2.0, we have seen very public criticism of the Fed and tweets and elsewhere, I think we've discussed and the PIMCO view is that, you know, the Fed has a lot of statutory insulation from Presidential criticism, which can help it to resist that pressure.

But certainly, you know, the, not only the ongoing criticism of Powell but statements from white hat officials that they're looking to see if they can remove Powell, the focus on the renovation.

And then most recently the Lisa Cook effort to dismiss Lisa Cook for cause, this is unprecedented. You know, it's probably hard for listeners to believe this, but the people that I know, they are just trying to get through meeting by meeting, they're really keeping their eye on the ball.

They do have this mandate from Congress. I do think that in perhaps an interesting way, the slowdown of the labor market data, and in particular the big revisions, you know, may have helped them to get to a consensus for a rate cut today, because I think it's pretty clear the labor market is flashing a signal that there is a case for the rate cut.

So the committee was more unified than I expected coming in today. I, as I said, I did think we could see additional dissents in addition to Miran on the dovish side, and maybe even some dissents on the hawkish side. So I take, we'll note, the transcripts will be available in five years, and Jay Powell may write his memoir in two or three [UNCLEAR], we'll actually know. But I would imagine, my sense is Powell on, in his phone calls with the individual members of the committee going into today, you know, made the case for Unity, you know, expecting that probably would get the dissent from Miran. And I think we saw evidence of that in the outcome, yeah.

GREG HALL: Right. And that I guess that speaks to some of the other governors where they may have disagreed in July about the precise, you know, start date of cuts or the magnitude of cuts still a close or a commitment to executing monetary policy, kind of away from political influence, or at least that is an interpretation.

I don't know if there's other possible ways of thinking about it that maybe a more cynical viewer may take. But it certainly seemed to me that it, there, like you said, the unity was a little tighter than folks were expecting. Do we know, actually, I wanted to ask you this question. Do we know for sure that the down 50 basis point dot plot was Miran's vote? Or are they anonymized and we're making an assumption?

RICH CLARIDA: No. The dots are anonymous until people start giving speeches on Friday. But we do know, because it was in the FMC statement that the dissent, there was one dissent in favor of 50 basis points today. And we do know that was Governor Miran. Yes.

GREG HALL: Yeah. Okay. Good. Good, good, good. See, these are the things I'm learning. I'm curious how, having been in the room. How contentious can these conversations get? How would you imagine you know, somebody who's, I mean, I don't actually, I don't, I really don't want it to presume any lack of objectivity or partiality or impartiality on Miran's part.

You know, he was confirmed by the Senate. He was appointed to the position following, you know, traditional process. But I'm curious about how the meeting operates and how much room there is for political versus economic dissent.

RICH CLARIDA: I would, well, I would be really, really, really surprised if when the transcripts come out, we'll see any reference to politics. You know, what you mentioned a moment ago, contentious, you know, I was there for four years, so I guess times eight, that was 32, 33 meetings. Contentious exchanges were rare, but not unheard of. But even the contentious wounds were pretty polite, and in part that's simply because you know, folks respect each other.

And oftentimes we'll come in and make the economic case for their policy rate call. So the Fed does something called an economic go-around where 19 folks will give their outlook for the economy in terms of inflation, employment and risk to the outlook. And so my strong belief is that Governor Miran, who voted in favor of the 50 basis point cut, spent the time during his economic go-around talking about the economic case for a 50 basis point cut.

And you know, and there is an economic case to make for a 50 basis point cut. So I would be surprised if there was anything that was contentious at this particular meeting. You know, I was at a meeting or two where it got contentious, but I don't think that was probably the case at this meeting.

GREG HALL: Well, I'm just doing the math here. Rich, I would imagine the transcripts from some of those are probably on their way out relatively soon.

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah. Well, in particular one transcript that one can look at, is from the 2019. So in 2019, the Powell Fed cut rates three times. And those transcripts are available. And in particular, you'll see that there were some pretty interesting interpretations or disagreements at the September of 2019 and October of 2019 meeting about those rate cuts. So those are out there now.

GREG HALL: And Powell himself, I think in his press conference afterward, was his, you know, I, in my note to myself, I wrote unflappable, which, you know, I think is a pretty, pretty good description of his public countenance and demeanor. Did you pick up anything, you know, in terms of his body language or, you know, his statement then about how he sort of felt about potential pressure coming from the White House at this point?

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah. You know, Greg, what I picked up was, I think after the revisions and the very week August employment data, that the 25 was, you know, 25 was a done deal. What was not a done deal was keeping the committee together and limiting the dissent to one vote. So the body language that I picked up, knowing Powell and knowing the players is the mission to accomplish for Powell was really in the phone calls that he had last week.

And in the run up to today's meeting, knowing that, you know, they actually didn't even know until maybe 48 hours ago that either Governor Cook or Miran would be there, but he had the deliverable for him was not the 25 that was gonna happen. The deliverable was keeping the committee together in favor of the 25 with the one dissent.

And so I think his body language was, you know, okay, we got that done and we move on to the next meeting. And that's why we got language in the press conference along the lines of, quote, it's not incredibly obvious what the Fed should do next. And he also downplayed the dots, you know, which Fed chairs Bernanke yelling can do. And this was a meeting where he actually said, look, we actually had nine of the 19 folks in favor of, you know, one or no cuts for the rest of the year. So he emphasized that as well.

GREG HALL: Yeah. Yeah. Oh, well, look, an evolving market that's data dependent is why we manage money actively, and reserve the right to make decisions and change our minds. Did anything in today's or in today's commentary or anything about the decision to do 25 basis points make you rethink previous thoughts around whether or not the White House might pursue replacing Powell prior to the ending of his term, or about maybe who they'd like to replace him with? Once, one, since Secretary Bessent has completed his search and they have a nomination to put forward any changes there?

RICH CLARIDA: Well, I was, you know, I have to confess, I was surprised that the Governor Waller did not dissent in favor of 50. I think there's an economic case to have gone 50. The economic case to go 50 is actually not dissimilar to the economic case to go 50 a year ago, which was that at the July meeting, they didn't cut.

And since then, the labor market data has been very disappointing. And had they known that they could have maybe argued for, you could have argued for 50 today, basically catching up with what they could have done in July. So I'll let others handicap whether or not, you know, this will help or hurt his chances to be Fed a chair. But I was surprised that he did not dissent in favor of a 50 basis point cut today. So I'll just leave it at that.

GREG HALL: Fair enough. Yeah. You had mentioned him, I think, in our February episode with you that you thought that Waller would not only be a candidate, but one that you respected and thought did a good job.

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah. And I continue to think, I continue to think that. Yeah.

GREG HALL: Excellent! I wanna move into a possibly a more philosophical realm here. And I say that as maybe warning to our listeners that if any of you are, you know looking, you know, more for the you know, the, just the facts and what happened today and market implications we're gonna move aside from that for a minute. Secretary Bessent published an opinion piece a little while ago in the journal accusing the Fed of ‘mission creep’. And I'd love to get your maybe distillation of what you thought his argument was, and then, and your reaction to it, especially having, you know, served as a vice chair yourself.

RICH CLARIDA: And 20 years ago it was a treasury official, although not Secretary of Treasury, so I know that building as well. Well, I read both. He actually did too. He did a journal piece, which was brief, and then he did a more extensive piece in a wonderful publication called The International Economy. And I read both of those. And there were several elements to the argument.

One, it's indisputable that the Fed's footprint in financial markets has expanded enormously compared to where it was pre global financial crisis. And so the Fed's balance sheet before the global financial crisis was under a trillion, I think $800 billion. And at one point it got to 9 trillion. So the Fed has a much bigger footprint in financial markets, both the size of its footprint. Also, the Fed is a very big holder of mortgage backed securities held zero of them in 2008.

And then he also criticized ‘mission creep’ in terms of some of the priorities, at least at the staff level of the green transition. And then also it was critical of some of the Fed's approach and its prior framework to emphasizing that maximum employment is broad based and inclusive. So there was a lot there. I think let's talk about the parts that are most relevant, I think, to investors, which are the criticisms about the size of the Fed's balance sheet, in particular, its footprint in mortgage market.

So, the Fed made a decision during my time formally in 2019, but this discussion had been ongoing for five or six years, that it wants to operate with what it calls an ample reserves framework, which essentially means that it once a financial system in which there's a lot of liquidity always in the system.

The alternative is the way the Fed implemented policy before 2008, which was in a scarce reserve regime, which is with a much smaller balance sheet, but much less liquidity in the banking system. So to give you one concrete example, and this is all sort of maybe technical, it's quite important. So one of the takeaways from the global financial crisis in the US and abroad was that we should operate our banking systems with much higher levels of high quality liquid assets in the banking system.

And so there's actually a high quality liquid asset requirement. And to put it in round numbers, big global banks in ’07 and ’06 had high quality liquid assets of around six to 8% of their balance sheet and now those numbers are around a quarter. And so the question is, if you're gonna require big banks to have liquid assets, where do they come from?

One possibility is that banks hold a lot of T-bills. And they do, and other possibility is they hold a lot of bank reserves. And so the system the Fed decided on in 2019 during my time, is we want banks to hold a lot of bank reserves that we create. The Fed created, we created when I was there, through a bigger balance sheet, so that's part of it.

The Fed could operate with a smaller balance sheet, and that would be a policy choice for the next Fed chair. The Powell Fed decided to run with an ample reserve regime, but that would be a choice. And over time, the Fed could operate with a smaller balance sheet.

Now, just as a footnote, we're not going back to an $800 billion balance sheet for the Fed, simply because there's a minimum size for the Fed balance sheet, and that's determined by currency and circulation because people have $2,800 bills, $5 bills in their pocket.

And right now, currency outstanding is about 2.5 trillion. So that's the minimum size for the balance sheet. On top of that, the Treasury Department has a checking account at the Fed, which is about nearly a trillion. So you add those together, the Fed's balance sheet can be smaller than it is today, but not going back to where we were before. So I think that's really the sort of the domain of discussion for the next Fed shares.

Do you get down to that minimum size? The other thing that's important is what is the maturity, composition of the Fed's balance sheet? How much do they hold in 10 year and 30 year treasuries, and how much they hold in bills. And that is something that for any given size of the balance sheet is also can be a factor and certainly Governor Waller has made the case that the Fed should get back to a balance sheet, which has a lot less duration on it and more towards the front end.

And again, that'll be a discussion for our future Fed. The final thing is mortgages. And here, I think this is really something that's important for our listeners to understand is the agencies, Fannie and Freddie before they were put into conservatorship in 2008, the agencies had very large retained portfolios.

They had a big footprint in the mortgage market, about a trillion and a half or so. Right now, the Fed's footprint in the mortgage market is around 2 trillion. So it's comparable to where the agencies were before they were put into conservatorship. And so over time, the Fed could reduce its footprint in the mortgage market. And a very important decision for the Fed to make, if it does this, will the agencies then pick up the slack and grow their retained portfolios.

And that will be a decision for Secretary Bessent and whoever is running housing and an agency policy. So I guess my bottom line is, we could think of a world where the Fed would operate with a smaller balance sheet, have a smaller footprint. We are not going back to the world of 15 years ago simply because of changes in the financial system.

But within those constraints, over time, the Fed may operate with a smaller balance sheet, and that will be up to, and a smaller footprint in the mortgage market. And that will be a decision for the future Fed chair and future Fed officials and the treasury to make over time. But those are the, I think, the market relevant aspects of the treasury's critique of gain a function monetary policy.

GREG HALL: I just, I want to note for the listeners that you still actively teach a class at Columbia on economics. So we've just heard from Professor Rich Clarida. I'd like to audit that class. That, I mean, that's incredibly fascinating. I did want to ask you, you know, as a follow on to that 'cause, and again, this, I probably my economics professors would be embarrassed by me asking this.

But in that same opinion piece that Secretary Bessent put out, he mentioned this sort of hither two unspoke of third mandate of the Fed, which was then again referenced in Steven Miran's confirmation hearing. And the third mandate being on top of price stability and maximum employment, which you've already referenced maintaining moderate long-term interest rates. And it's interesting in its own right that they've chosen to emphasize that at this moment. And then in the context of Secretary Bessent decrying the use of the Fed balance sheet, I wonder if those were contradictory or if there's some through line that I'm missing?

RICH CLARIDA: Yeah. Well, you know, it's a fascinating question, and it's certainly something that we used to talk about a bit at the Fed. Now, Ben Bernanke, former member of our global advisory board at, in one of his many comments as an official and I'm paraphrasing, but it's pretty close to the exact quote.

Ben was asked that question once, and his answer was, the Fed does have a triple mandate and moderate long-term interest rates is in the statute, it's not, you know, you don't have to like look at tea leaves. It says in black and white moderate long-term interest rates.

And Ben's answer, which I think if you ask most Fed officials and staffers would be the answer they would give is the Fed has a price stability objective. And so, if the Fed delivers on price stability, let's say 2% inflation over time, then that will deliver moderate long-term interest rates as a benefit of having moderate and low and predictable inflation.

So if you get low inflation and you have stable inflation, you don't have a big inflation risk premium, as was in the market when I began my career in the 1980s. And so the standard Fed answer is, if you do your job in inflation, moderate long-term interest rates will sort of be delivered as a benefit of that. But, there are others who could take the position that the Fed should be, you know, more active in achieving that.

And you very correctly point out, if you took my class, you get an A for that answer, that perhaps there is some tension between having saying, we want the Fed to be more aggressive in delivering moderate long-term interest rates. Oh, and by the way, we want you to have a small balance sheet. So, yeah. And then you, again, maybe to be too professorial, but if you go back to the last time that the Fed really did outsource its policy to the treasuries desires was the 1940s.

And the ideal was without any White House pressure, the Fed made a decision, you know, what we, there is a war, we're at World War II, and our part for the war effort is we're gonna keep bond yields low. So they essentially did yield curve control, and they put a cap on treasury yields.

And as I say, when I talk to students about this, the Fed sort of didn't get the memo that World War II ended in 1945, and they kept pegging treasury yields until 1951. And that's the very famous Fed treasury accord in which the Fed declared independence from the Harry Truman Treasury. And it was very disruptive and divisive, and ultimately the Fed did declare independence, but it took six years after the end of the war to actually move away from that moderate long-term interest rate focus.

GREG HALL: Well, and that's another good reminder of cycles and that history, you know, it doesn't repeat, but it rhymes.

RICH CLARIDA: Right!

GREG HALL: So thank you, Professor Clarida! We really appreciate it!

RICH CLARIDA: Well, thank you for having me!

GREG HALL: Oh, yeah. And Thanks for making time again on such a busy day. Thank you for, you know, devoting time and effort to our clients here. And hopefully readers listening to this will walk away not just with a, you know, a great kind of near term impression of everything that went on today, but also, you know, just a masterclass in, you know, some of the broader kind of philosophical and structural issues that are gonna affect decisions over the course of the next few months.

RICH CLARIDA: Thank you!

GREG HALL: Thank you, Rich!

All right. So that was my conversation with Rich Clarida, former Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve on Fed Day. Really nice of him to carve out some time to spend with us amidst a very busy calendar. I hope you found it as enlightening as I did both as it relates to the immediacy of today's decision and what it might mean as well as, you know, some of the historical conversation we got into and the historical precedence that lead us to a lot of the issues and challenges and balancing act that we find today.

We will look forward to speaking to you again on the next podcast next month. And in the meantime wish you all, you know, a terrific fall season and a great rest of the month!

From This Episode

- The Fed’s decision-making process.

- Reading signals: Thoughts on shifting patterns around trade, labor markets, inflation and more.

- Fed independence: Thoughts on Cook, Bessent, Miran, and others.

- What is it like being in the room?

Read our FOMC Insights: Fed Delivers Dovish Shift, Restarts Rate-Cutting Cycle.