What are corporate bonds?

When companies want to expand operations or fund new business ventures, they often turn to the corporate bond market to borrow money by issuing bonds.

The company determines how much it would like to borrow then issues a bond offering to investors in that amount. Investors who buy the company’s bonds effectively lend money to the company according to the terms established in the bond offering or prospectus.

Unlike with equities, ownership of corporate bonds does not signify an ownership interest in the company that has issued the bond. Instead, it signifies ownership of a company’s debt. The company pays the investor a rate of interest over a period of time and repays the principal at the maturity date established at the time of the bond’s issue

While some corporate bonds have redemption or call features that can affect the maturity date, most corporate bonds are loosely categorized into the following maturity ranges:

- Short-term notes (with maturities of up to five years)

- Medium-term notes (with maturities ranging between five and 12 years)

- Long-term bonds (with maturities greater than 12 years)

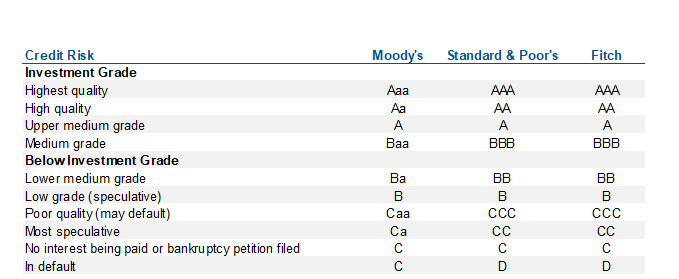

In addition to maturity, corporate bonds are also categorized by credit quality. Credit rating agencies such as Moody’s Investors Service and Standard & Poor’s provide independent analysis of corporate bond issuers, grading each issuer according to its creditworthiness. Corporate bond issuers with lower credit ratings tend to pay higher interest rates on their corporate bonds.

How are corporate bonds rated?

The corporate dividing line: investment-grade and speculative-grade. Corporate bonds fall into two broad credit classifications: investment-grade and speculative-grade (or high yield) bonds. Speculative-grade bonds are issued by companies perceived to have a lower level of credit quality compared to more highly rated, investment-grade, companies. The investment-grade category has four rating grades while the speculative-grade category is comprised of six rating grades.

Historically, speculative-grade bonds were issued by companies that were newer, were in a particularly competitive or volatile sector, or had troubling fundamentals. Today, there are also many companies whose businesses are designed to operate with the degree of leverage traditionally associated with speculative-grade companies. While a speculative-grade credit rating indicates a higher default probability, these bonds typically compensate investors for the higher risk by paying higher interest rates, or yields. Credit ratings can be downgraded if the credit quality of the issuer deteriorates, or upgraded if fundamentals improve.

Fallen angels, rising stars, and split ratings

“Fallen angel” is a term that describes an investment-grade company that has fallen on hard times and has subsequently had its debt downgraded to speculative grade.

“Rising star” refers to a company whose bond rating has been increased by a credit rating agency due to an improvement in the credit quality of the issuer. Since the credit rating agencies’ ratings are subjective, there are also times when they do not concur on the rating – an occurrence known as a “split rating.” Fallen angels, rising stars, and split ratings may all present opportunities for investors to add additional yield by assuming greater risk due to the potential volatility of their ratings.

How are corporate bonds priced?

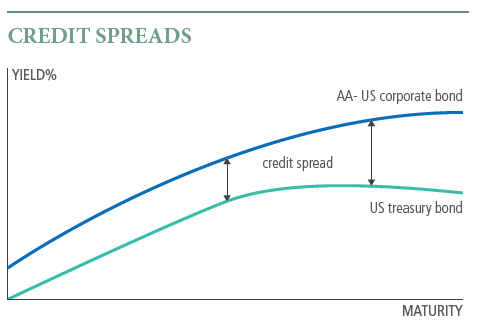

The price of a corporate bond is influenced by several factors, including the maturity, the credit rating of the company issuing the bond, and the general level of interest rates. The yield of a corporate bond fluctuates to reflect changes in the price of the bond caused by shifts in interest rates and the markets’ perception of the issuer’s credit quality. Most corporates typically have more credit risk and higher yields than government bonds of similar maturities. This divergence creates a credit spread between corporates and government bonds, so that the corporate bond investor earns extra yield by taking on greater risk. The credit spread affects the price of the bond and can be graphically plotted and measured as the difference between the yield of a corporate and government bond at each point of maturity.

Why invest in corporate bonds?

Corporate bonds can offer a range of potential benefits including:

- Diversification: Corporates offer the opportunity to invest in a variety of economic sectors. Within the broad spectrum of corporates there is a wide divergence of risk and yield. Corporate bonds can add diversification to an equity portfolio as well as diversify a fixed income portfolio of government bonds or other fixed income securities.

- Income: Corporates have the potential to provide attractive income. Most corporate bonds pay on a fixed semiannual schedule. High yields can enhance this income stream, especially in a low-interest rate environment. However, these yields are also influenced by the bond’s coupon rate, current market price, and the credit risk of the issuing company. For instance, a higher yield may indicate a higher income stream but could also reflect higher credit risk. One exception is zero-coupon bonds, which do not pay interest but are sold at deep discounts and then redeemed for full face value at maturity. Another exception is floating-rate bonds that have fluctuating interest rates tied to a money market reference rate such as the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) or federal funds rate. These tend to have lower yields than fixed-rate securities of comparable maturities but also less fluctuation in principal value.

- Higher yields: Corporate bonds tend to provide higher yields than comparable maturity government bonds.

- Liquidity: Corporate bonds can generally be sold at any time prior to maturity in a large and active secondary trading market.

What are the risks?

Similar to government bonds, corporate bonds are exposed to interest rate risk. In addition, corporate bonds also have spread risk or default risk - the risk that the borrower fails to repay the loan and defaults on its obligation. The level of default risk varies based on the underlying credit quality of the issuer.